Welcome to the latest installment of my monthly advice column. Weigh in with your own advice here.

Dear Subtle Maneuvers,

I’m lucky enough to be a working writer and radio maker (podcaster? producer? the name of that job always eludes me) and for years have been on a constant hunt for a daily routine that will allow for the perfect combination of artistic magic and no-nonsense productivity. When I’m in the middle of a project, I can usually find something that works, but where I struggle is when I finish something. I just turned in the first draft of my first book to my editor. It is a huge accomplishment, of course, but it has left me bereft. I know I need a break (by the end of the draft I was really limping along) and I know I should celebrate. Covid, of course, has made both those things difficult. But even in non-Covid times, I always get a little depressed after the exultation of completion. I sometimes call this phenomenon le petite mort after the French euphemism for orgasm. I sit around for much too long, worried I’ll never make anything again, fearful that there is nothing left in my creative brain, terrified I’m a failure. I was really looking forward to working on some personal essays in this time while I wait for my editor’s notes, but every time I sit down to work on them, I can’t find the juice and then I just feel terrible.

Although I assume I’ll get over it in a few weeks, or a month, I have to say that this process is pretty inefficient! And although taking a few weeks of self-indulgent angst after a big project was OK as a young, free-wheeling person, now I’m 37 and hoping to have a baby soon, and feeling anxious about how the pressures of time will push down on me even more when I have a small infant and as I get older (shouldn’t I have done MORE by this point?). So, I suppose my questions are: What do you recommend when finishing a creative project? How do you enjoy it? How do you not fall into a pit of depression? And then... Do you have any recommendations for thinking about new motherhood and a creative life?

—Heather in Brooklyn

Dear Heather,

Thanks so much for your letter, parts of which felt so familiar that it was a little uncanny. I, too, am on a “constant hunt” for that “perfect combination of artistic magic and no-nonsense productivity.” And I, too, really struggle at the completion of a big project. After both of my Daily Rituals books were done, I felt a brief surge of elation followed by long periods of torpor, listlessness, lack of conviction, lack of direction, you name it.

You may take some comfort, as I have, in hearing that this is extremely common and perhaps inevitable. Partly it’s sheer physical and mental depletion, which I think you have to expect. Writing is a major cognitive challenge, and getting through an entire book draft means marshaling a huge amount of energy; of course you’re going to feel run-down afterward!

Interestingly, the best descriptions I’ve found of this run-down state come from painters. Helen Frankenthaler, for instance, said: “I tend to focus on a body of work intensely and one day put down the brush and feel emptied out.” A small break could be refreshing, she said, but a long one was frightening:

I will often get back to painting after a break and panic and not know where I left off. I seem to start at day one again. I sit around and sharpen pencils, make phone calls, eat handfuls of pistachios, take a swim. I feel I should, must, will paint. It is agony. It is boredom. I become impatient and angry with myself, until I reach a point of feeling I must start, make a mark, just make a mark. Then, hopefully, I slowly get into a new phase of work.

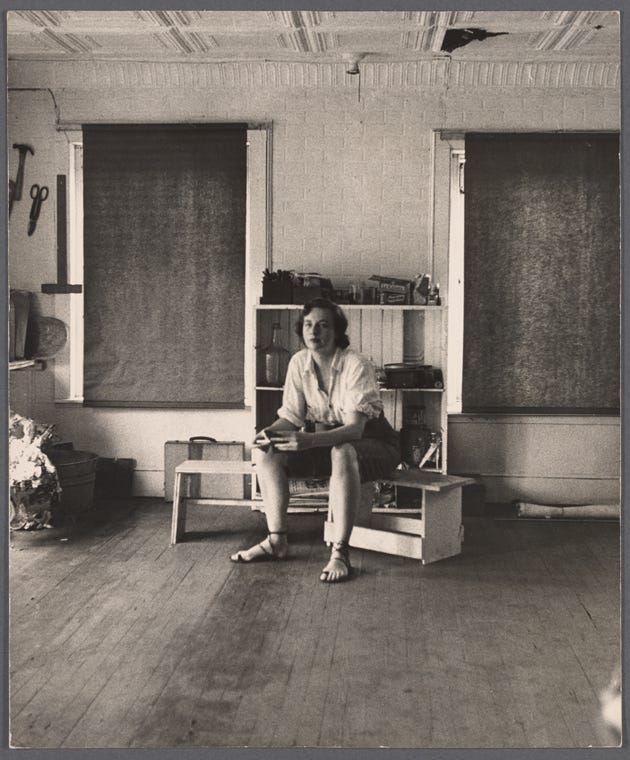

In a similar vein, the painter Grace Hartigan wrote the following in her journal in January 1955:

I am in one of those terrible times when I feel “painted out.” I alternate between ennui and restlessness—an ennui that stupefies me, keeps me curled in my chair for hours and hours, reading anything—movie books, detective stories, “literature,” old journals. Or the restlessness that makes me walk the floor, staring out one window and then another, or sends me dashing into the street to stare into people’s faces or dash from one gallery to another, or pace frantically through museums looking for what, some clue, some hint, anything thing in life or art that will get me out of this pit.

What Frankenthaler and Hartigan are describing is depletion, yes, but also loss—another probably inevitable feeling when you complete a project that’s been central to your life for months or years. It’s interesting that you reference la petite mort, literally “the little death.” I do think there’s a bit of grief tied up with the completion of a big project, even if you’re also excited and relieved to be done with it. And there may also be a taste of your own mortality, the feeling that even after you’ve exerted so much energy and intelligence and judgment to create something out of nothing, the world pays hardly any notice and keeps on turning, with or without you and your works.

Or maybe it’s not that complicated. There’s a line in Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness: The End of a Diary that feels apt here: