Alice Neel on painting, money, and Russian caviar

Notes on the brilliant and idiosyncratic American artist

Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Previously: Byron and Shelley’s daily routines circa 1822.

Alice Neel (1900–1984)

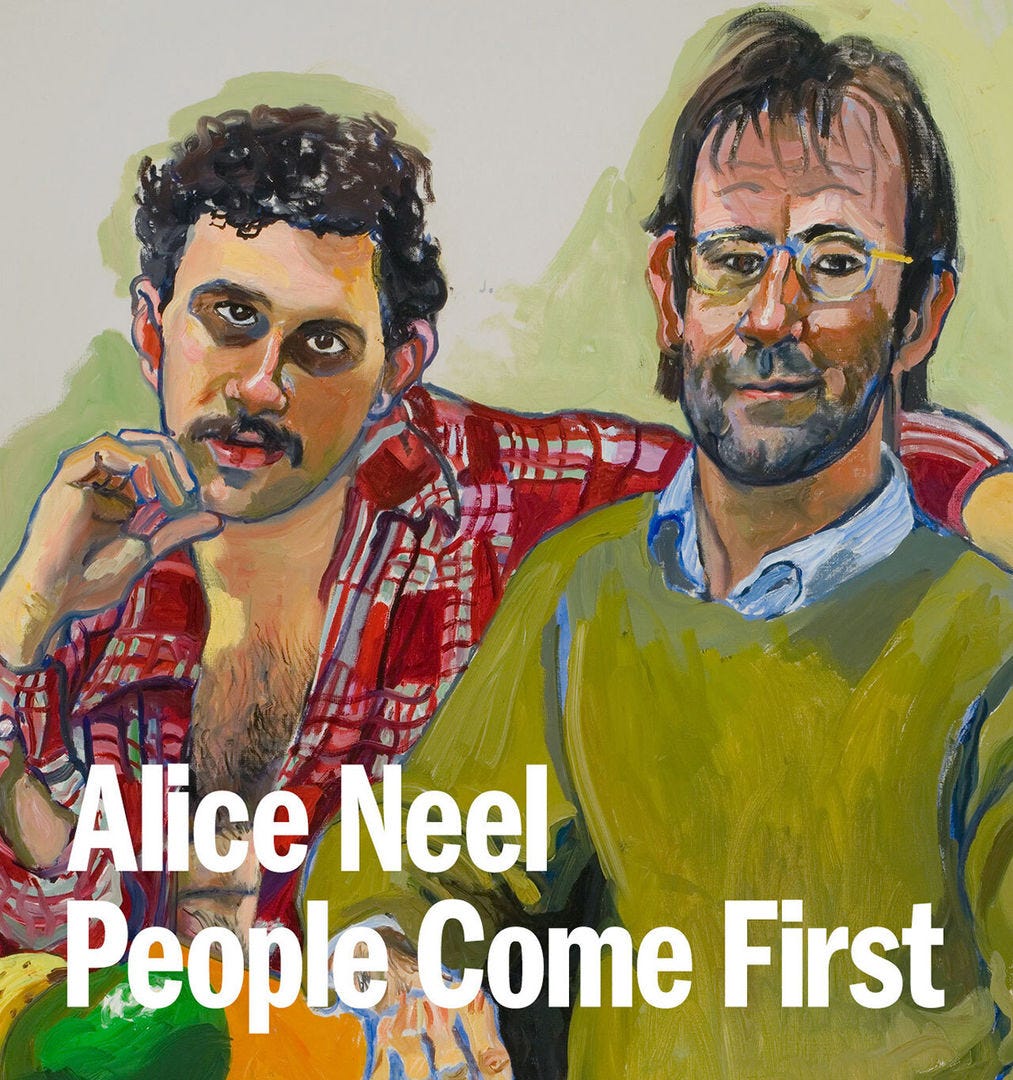

These last several weeks, I have not felt too jealous of all my friends and family members who have been getting vaccinated while I’m still waiting for the shot (soon!)—but I have felt jealous of those friends in New York who have taken advantage of loosening Covid restrictions to go see Alice Neel: People Come First at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After a year of barely seeing other humans in the flesh, how glorious to walk up the steps of the Met and find your way to dozens of Neel’s vibrant, fleshy portraits, to see all those faces and bodies on full, unself-conscious display. Actually, it sounds a little overwhelming—but in a way that would invigorate the system, like jumping into an icy pool after spending too long in a confining sauna.

In Daily Rituals: Women at Work, I wrote a single paragraph about Neel’s daily painting life, and, to be honest, I never felt totally satisfied with how it came out. Here I thought I’d share some more of what interests me about Neel and her working life: