Relationship goals with Bernd and Hilla Becher

“You can exchange ideas and it feels less bleak when you are in some god-forsaken place.”

Since everyone seemed to enjoy Tove and Tooti’s cottage life last time, I thought I would turn to another successful creative partnership: that of the German husband-and-wife photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931–2007; 1934–2015), who are currently the subjects of a retrospective on view at the Met until November 6.

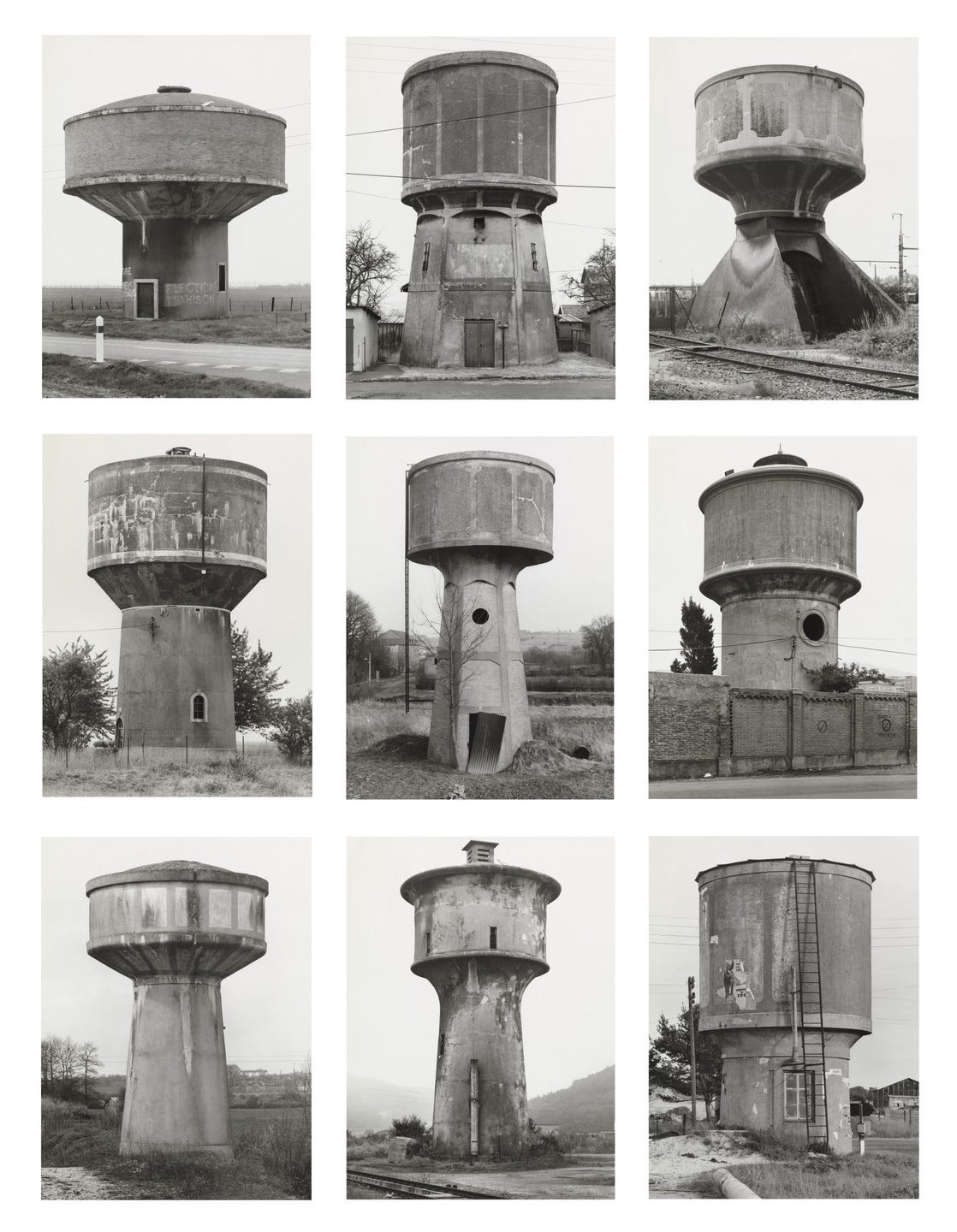

I’m guessing that many of you are already familiar with the Bechers’ work: Over decades, they photographed water towers, blast furnaces, grain elevators, cooling towers, lime kilns, gasometers, and other components of industrial architecture in rigorously precise black-and-white images that they later gathered into “typologies.” Grouped together, these stoic compositions became something else entirely—a witty, profound survey of human endeavor and its inherent beauty, goofiness, and/or pathos, depending on your mood.

At first glance, you might guess that these photographs were relatively easy to take; just set up a tripod, click, repeat. In fact, the Bechers went to extraordinary lengths to capture them. Every stage of the process involved hurdles, from getting permission to photograph active industrial sites to finding the right angle—the Bechers preferred to shoot from slightly above, which often meant climbing a nearby structure—to attaining specific light conditions. “We preferred very soft light,” Hilla said in a 2015 video. “If the light was too harsh we had to wait for a cloud or we had to wait for the winter or we had to wait for dawn.”

As for their working partnership, the Bechers did not rely on any set division of labor. Whether they were in the field or in the darkroom, each partner did whatever needed to be done, more or less interchangeably. In a 2004 interview, a journalist asked the Bechers, well, why exactly do you work together? I find their reply hilariously matter-of-fact:

Could you now take the shots you took together alone? What difference does it make going about this together?

Bernd: None. But everything is easier to handle as we help each other.

Hilla: Traveling together is simply more pleasant.

Bernd: Also considering all the lugging this entails. We have to climb and some of our photographing positions are quite dangerous and difficult to reach. All this is considerably easier to manage with two of us.

Hilla: In some of the blast furnace plants it is one of the conditions that two people are there together owing to the danger of toxic gases. If something were to happen to one of us, the other could always get help. But there are other reasons why we do this together. When you are traveling together you can exchange ideas and it feels less bleak when you are in some god-forsaken place—like when we spent weeks traveling through the American Midwest. The nights in shabby hotels are more comfortable when you are with somebody.

At the end of the day, isn’t that what we’re all looking for in a relationship? Someone who will make the nights in shabby hotels more comfortable and also go for help if we succumb to toxic gases.

FINALLY WE ARE ABLE TO GO AHEAD

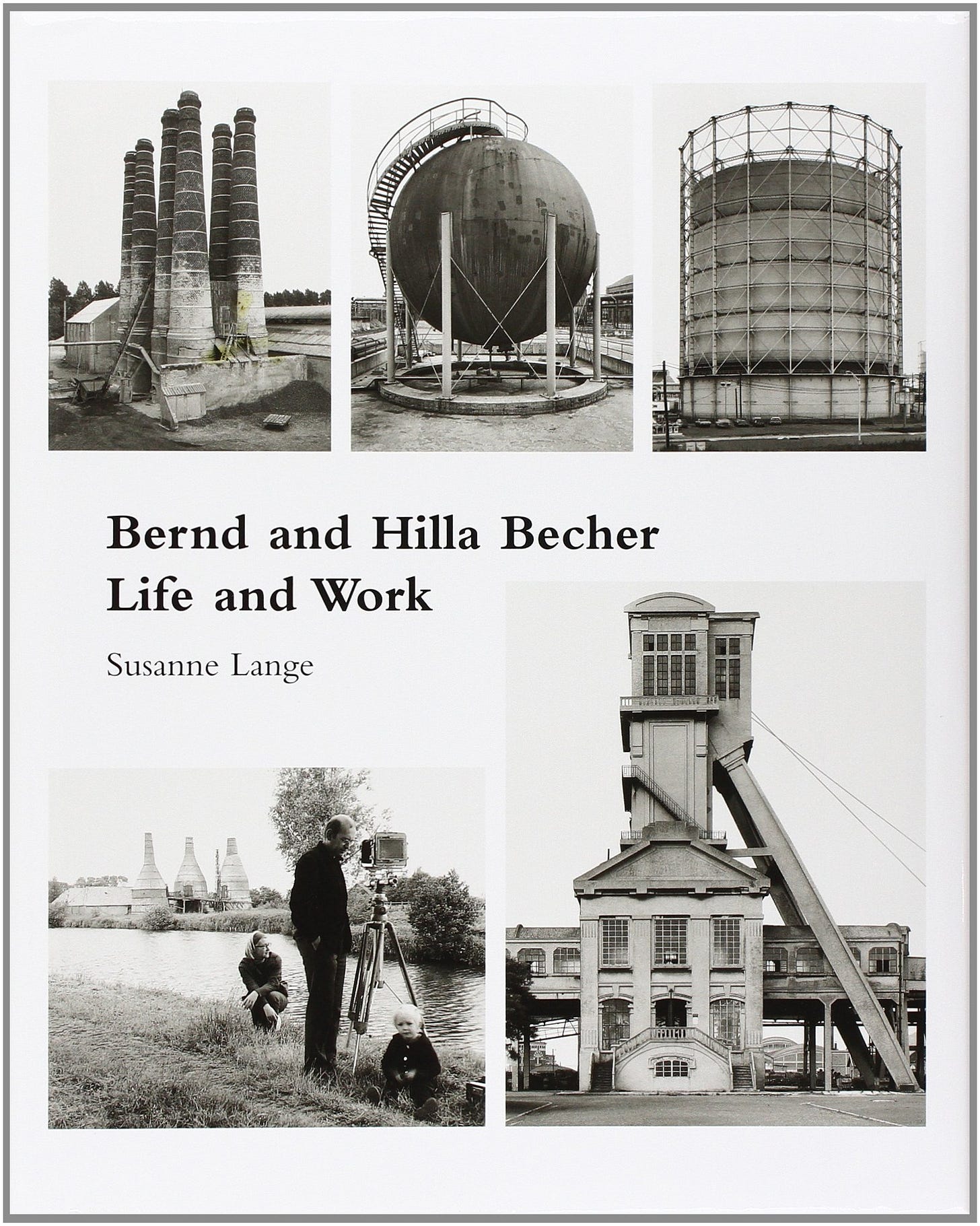

I found the above exchange in Susanne Lange’s Bernd and Hilla Becher: Life and Work. The book also reprints some of the notes that Hilla Becher made during their travels, and these provide a fascinating glimpse of the day-to-day reality of their work.

Here are a few excerpts from Hilla’s notes during the couple’s travels in the United States in the early 1980s:

Friday, May 23, 1980 (Pennsylvania)

With permission from J & L we drive to the Nemacolin Mine. I go to the office alone but the manager still asks a lot of questions. Finally we are able to go ahead and from this point on nobody disturbs us all day. . . . On the left side some bushes have grown in front of the building. We ask the engineer cautiously if we can saw down the bushes and he replies that they were thinking of doing it anyway as they want to build a cooling pond there. We set to work with the good old Swedish saws.

Tuesday, September 27, 1983 (Alabama)

Today was a grim day. Not only did we have lots of bad luck but we also miscalculated the weather and were too late to notice that the afternoon would have been perfect for taking photographs.

In the morning we start to develop yesterday’s films. In the daytime we have the problem of not being able to get the bathroom properly dark. Apart from the bathroom window we also block the corridor window with the second mattress from the car. Around midday we notice that the mattress has slipped and has started to burn (from the lamp underneath). It looks harmless and we pour water over it, but it continues to smolder within, Bernd then wets it thoroughly and places it on the car as it already stinks so terribly inside. It continues to burn—so we put the whole thing in the bath and finally Bernd has to drive off and get rid of the corpse (in a supermarket garbage container).

Saturday, October 1, 1983 (Alabama)

Sun and a little mist. It could be fine for the high-rise. . . . Mr. Arnold unlocks the door but doesn’t come with us. The building is actually empty, most of the doors and some of the windows are open, we fear that there could be some squatters here as we keep hearing noises. In order to bring all the equipment up we have to climb the ten (or eleven) floors twice. Up above we have three choices. The top one is out of the question as there is a hornets’ nest at the end of the vertical ladder. I have never seen behemoths of this size before. . . .

I AM A WORKER TOO!

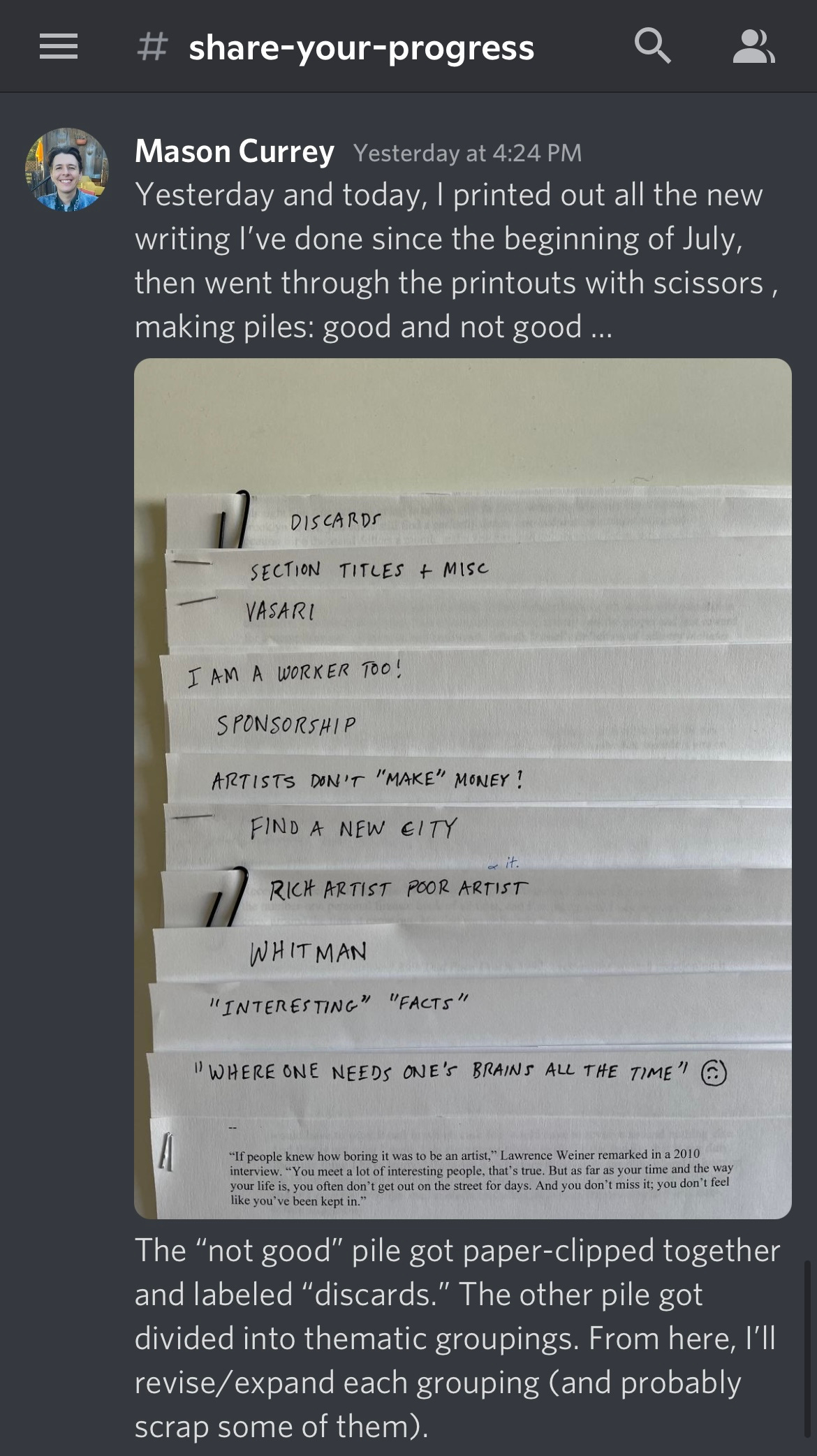

Over on the subscriber-only Discord, I’ve been sharing a bit about the (extremely halting) process for writing my next book . . .

. . . and I’ve been enjoying chatting with readers about their creative triumphs and struggles (and also sharing photos of our dogs). Come join us! Access to the Discord** is one of the perks of becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter. (OK, so far it’s the only perk, other than my sincere gratitude for your support!)

**If you’re intimidated by Discord, don’t be: It’s basically like an old-school chat room, where you can drop in as you feel like it and share whatever’s on your mind.

NOSTALGIA + CLARITY = ART?

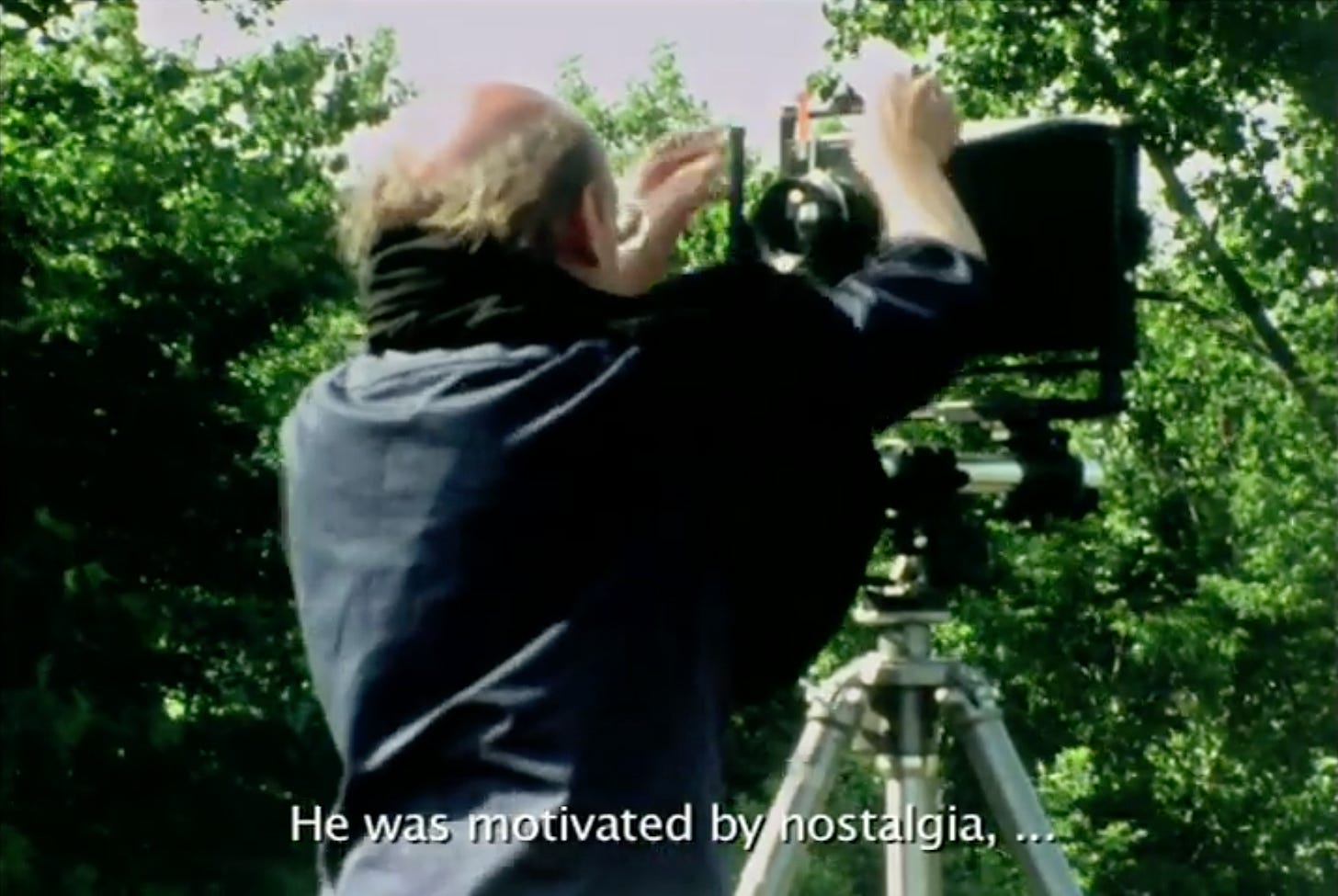

One last word on the Bechers’ artistic partnership, from their son, Max Becher:

(Screengrabs from a 2012 documentary by Marianne Kapfer)

Thanks for reading! This newsletter comes out every other Monday—and you can help keep it coming by becoming a paid subscriber, buying one of my Daily Rituals books, forwarding the newsletter to a friend, or even just clicking the “like” button below.

Love their unsentimental work while being so sentimental about doing things together.

"Someone who will make the nights in shabby hotels more comfortable and also go for help if we succumb to toxic gases" 😂😂😂 ...SO ROMANTIC.

I for one was not familiar with the Bechers, so thank you! I love these (what seem like) portraits of these monolithic structures. Hard core.