My next book is all about how creative people through the ages have funded their creative work, whether through day jobs, parallel careers, patronage arrangements, get-rich-quick schemes, petty theft, or other subtle and not-so-subtle financial maneuvers. (It comes out next March; I’m excited to do a cover reveal and share the pre-order link in the coming months!) And if there’s one trait that extends across nearly all of my subjects, it’s a kind of practical impracticality: a consistent refusal to do the pragmatic, socially acceptable, or fiscally responsible thing when doing so conflicts with one’s deepest creative impulses.

So I was delighted last week to listen to an interview with Courtney Love—one of the mythic figures of my grunge adolescence—articulating this attitude in a succinct and memorable way. She was talking with Bella Freud for Freud’s wonderful Fashion Neurosis podcast, and the conversation turned to what other career Love might have pursued if music hadn’t panned out:

Love: If I didn’t do what I did, I’d probably be a costume designer. Which—I never wanted a plan B, and when I got offered that job, I literally threw it at a friend. Because if you have a plan B, you’re gonna do the plan B. That’s always a truth.

Freud: Yeah, it’s so true. That’s such a good tip: Don’t ever have a plan B.

Love: It’s really the truth. If you have a plan B, you’re going to do it.

Don’t have a plan B! I realize this is the exact opposite of the advice that most parents would give a child considering a career in the arts; I realize that they would very sensibly advise a young aspiring writer or painter or musician to also get a degree in accounting or librarianship or some other practical field as a fallback option—but, more and more, I agree with Love and Freud that that is precisely what one should not do when one is young and full of energy and ideals. There will always be a fallback option later. There is only one period in your life when you’re unburdened and optimistic enough to see what interests you and then simply start doing it, without too much knowledge about how it’s been done before or how slim your chances are at “making it” in that field. And the real trick, I think, is to hang on to that optimism and sense of possibility, and not let the world beat it out of you.

Or am I being overly optimistic? I’m curious: Are there are any artists or writers or musicians reading this who wish they had gotten that accounting degree back when they were just starting out? As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences in the comments section below.

DON’T HAVE A PLAN B — AND ALSO DON’T GET A JOB?

Courtney Love’s advice reminds me of Brian Eno’s favorite piece of advice for young artists, which he recounted in a 2015 lecture:

Eno says:

I often get asked to come and talk at art schools, and I rarely get asked back, because the first thing I always say is: I’m here to persuade you not to have a job. And the professors always look a bit nervous at that point, since they often consider that their task is to somehow smooth you into a job. My first message to people is: Try not to get a job. That doesn’t mean try not to do anything. It means try to leave yourself in a position where you do the things that you want to do with your time, and where you take maximum advantage of whatever your possibilities are.

Eno goes on to acknowledge that, of course, “most people aren’t in a position to do that”—which is why he’s a vocal proponent of universal basic income, which he calls “the closest thing I’ve heard to achieving the kind of future that I would like to live in.” Hear, hear.

WORM SCHOOL EXTENSION

Quick reminder that I’m currently writing a series of bonus posts for paid subscribers, reflecting on the five things that helped me finally, actually, for-real get my long-overdue book project done. The first two parts are below; the next one arrives this afternoon, with two more to follow in the coming weeks.

Writing this series has been an interesting challenge: It’s meant trying to unpack what really was helpful for me in getting the book done, and then trying to distill those things into actionable lessons for anyone to try. Here are the first two lessons:

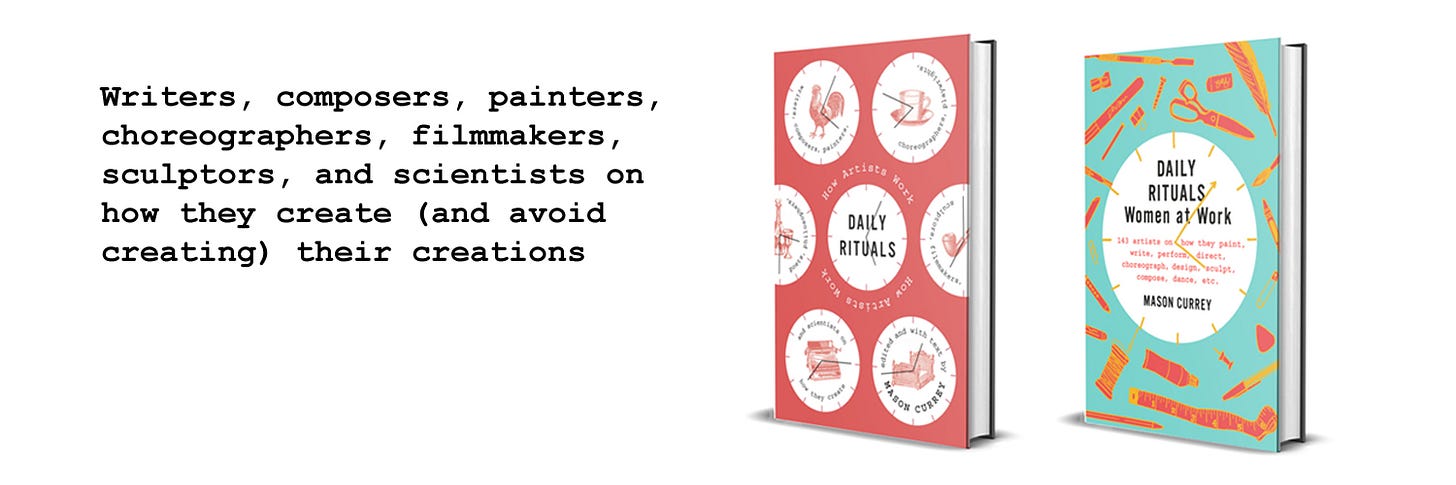

Thanks for reading! This newsletter comes out every other Tuesday—and you can help keep it coming by upgrading to a paid subscription, buying one of my Daily Rituals books, forwarding this email to a friend, or even just clicking the “like” button below.

I was a Plan B-er and stuck at it for 40 years, rising to the top of my profession. Plan A was always in my mind and now I'm in my 60s, I'm following it. Positives? I earned enough to save for my later years so don't worry about money. Negatives? Being a late starter isn't easy, and I lost 40 years of creativity. Do I regret what I did? Yes and no. My career was not in the creative arts, but I met so many interesting people that I wouldn't otherwise have met and did worthwhile things that taught me about life, so good. If I had success at a young age in the arts (I'm now a writer and editor) it would have been good, but if I didn't get anywhere I would have had a job that didn't challenge me and helped me grow. Swings and roundabouts.

I think "Plan B" jobs can teach you skills you need for Plan A. Working in production and fundraising for a theater helped me run my own independent festival later on. And teaching writing has made me a better writer. I don't think it's as binary as "no back up" to prevent you from going full force on your dream, maybe it's helpful to think of other jobs as a means to acquire the skills and practice for your dream job. Like a musician who works in audio mixing, which will only help them with their own music.