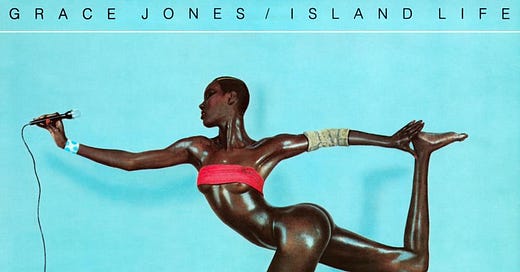

Welcome to the 13th issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Last week: productive puttering with Angela Carter. This week: shucking oysters with Grace Jones.

Grace Jones (b. 1948)

The Jamaican–born singer, songwriter, and style icon turns 72 tomorrow, and her birthday seems like a good excuse to take a look at her contract rider, which lays out the precise conditions necessary for hosting the performer and her entourage (and which was printed as an appendix to her 2015 book I’ll Never Write My Memoirs). Here, for example, is the list of essential items to be placed in Jones’s dressing room: