Hayao Miyazaki, creativity, and selfishness

Watching a four-part documentary on Japan’s irritable genius of animation

Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Previously: Finding “energy, energy, energy” in your creative life.

Hayao Miyazaki (b. 1941)

Last week, in honor of the legendary Japanese filmmaker’s 80th birthday, I watched a four-part, three-hour-plus documentary about Miyazaki’s creative process produced by the country’s public broadcaster, NHK (and streaming for free on its website and iOS app). It was a good choice. From the very first frames—when Miyazaki pulls up to his private Tokyo studio in a pristine Citroën 2CV with folding side windows (!)—I knew I was in for a treat.

The documentary begins (as all artist docs should?) with a look at Miyazaki’s unvarying morning routine: He arrives at his studio at 10:00 a.m., lets himself inside, and shouts “Good morning!” into the empty rooms. When asked whom he’s greeting, Miyazaki replies: “The residents. . . . Don’t know who they are, but they’re here.”

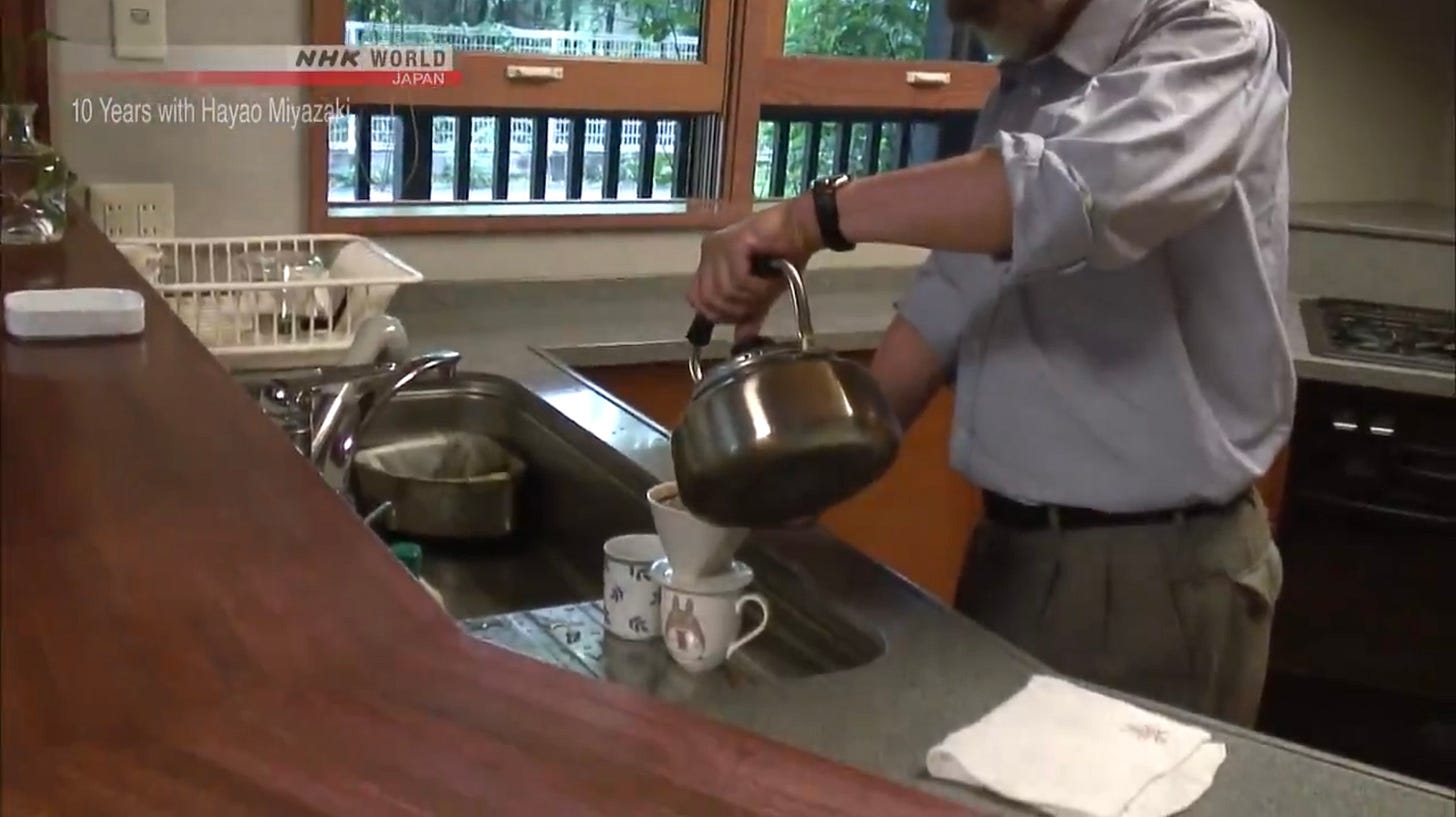

After going around opening doors and curtains throughout the building, Miyazaki makes himself a cup of pour-over coffee and, with the help of an assistant who has arrived, carries out a wooden bench to a designated spot in front of the studio. “Have a seat,” reads a sign on the bench. “The trap is set!” Miyazaki chuckles. From a window upstairs, he can observe anyone who takes him up on his offer.

For those unfamiliar with Miyazaki, he is the cofounder of Studio Ghibli and the creator of a string of internationally beloved animated films, including Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke. The NHK documentary follows him over the course of seven years, spanning the conception and execution his final two features, 2008’s Ponyo and 2013’s The Wind Rises, after which he announces his retirement.

It’s no surprise that the film has been a favorite among Miyazaki meme-makers: The ritual-loving, publicity-hating, perpetually self-doubting creator hunched over his tiny drawing desk, depositing draft after unacceptable draft into his overflowing wastebasket, and smoking cigarette after cigarette while dispensing nuggets of insight into the creative process—well, it’s pretty irresistible for anyone who has grappled with the same halting, extravagantly frustrating process.

Not that Miyazaki comes off as entirely lovable. He clearly enjoys his role as an irritable creative genius being catered to by an obedient staff. He admits to being an absent father when his eldest son, Goro, was young. Worse, he is openly hostile toward Goro’s own filmmaking efforts, and even seems to relish his mistakes, using them as opportunities to encourage Goro to quit the profession entirely. (The scenes of the forty-something son trying to carry forward his own vision in spite of his father’s withering attitude are painful to watch.)

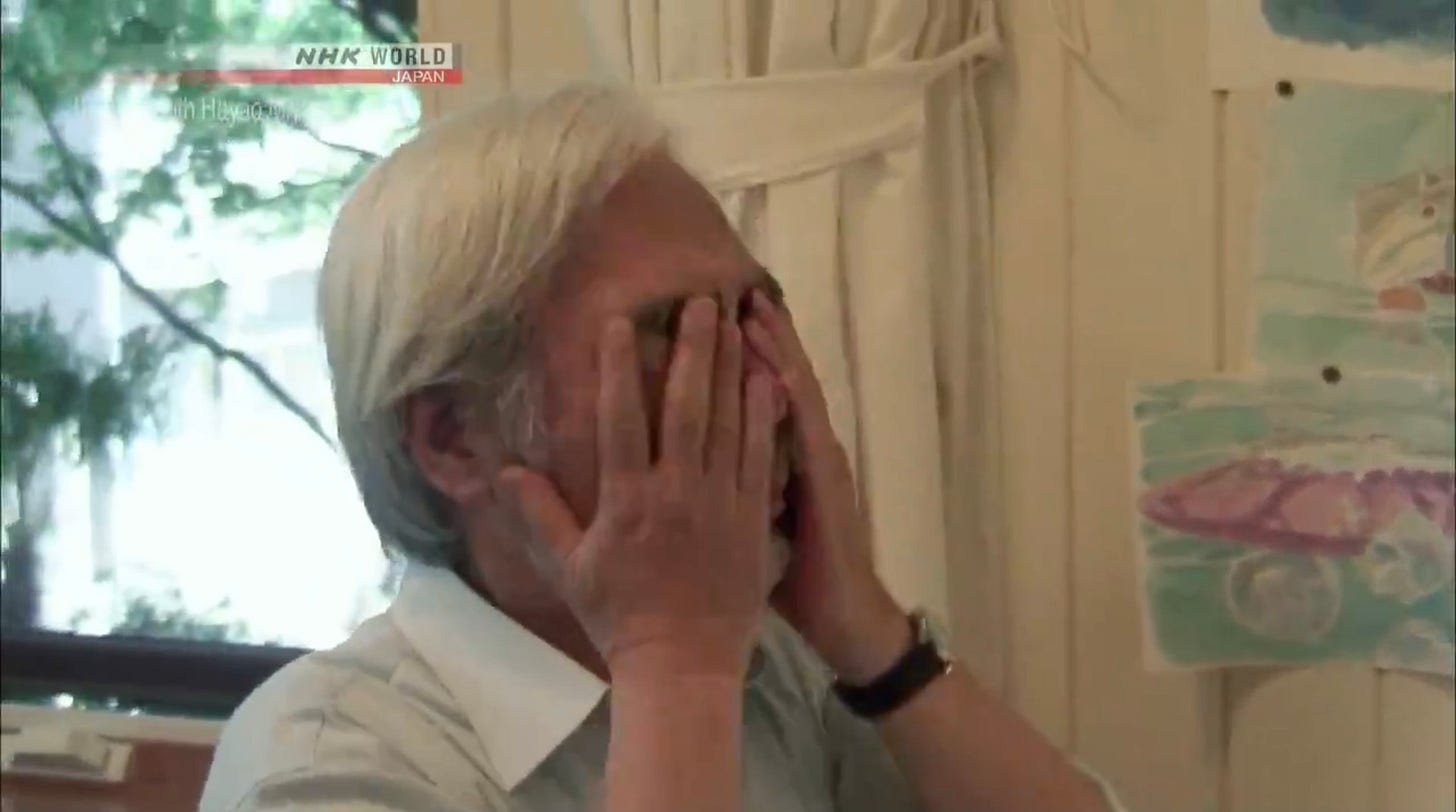

Even so, I found a good portion of Miyazaki’s scenes all too relatable. I don’t think anyone gets a pass for being a selfish jerk—but any ambitious creative pursuit does require an element of selfishness, and Miyazaki comes across as a grumpy avatar of this inward-turning, solitary side of the process. He is the melodramatically tortured, crabby-old-man figure in us all, tossing yet another subpar page into the bin, pulling off his glasses and running his fingers through his cloud of white hair (stained yellow by the cloud of cigarette smoke hovering over his desk) before sighing dramatically and turning back to it once more.

PLEASE DISCUSS

What do you think—is selfishness an inherent part of the creative process? Or is that just a convenient excuse for being selfish? Leave your thoughts in the comments below and I’ll be reading and replying this week.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS IN 43 HAYAO MIYAZAKI SCREENGRABS

Watching the documentary, I couldn’t stop taking screenshots of Miyazaki’s creative ups and downs (OK, mostly downs), which I compiled into a Twitter thread that you can preview below or view in its entirely here.

MORE ON HOW MIYAZAKI WORKS

Last year, Kotaku published an excerpt of a memoir by a Studio Ghibli executive that includes a detailed description of Miyazaki’s filmmaking process, beginning as follows:

Hayao Miyazaki’s way of making a film was particularly stressful, and that was exactly how he thought it should be. He would often say that a person only does his best work when faced with the real possibility of failure and its real consequences. Several times after the completion of one of his films, Miyazaki would suggest that the studio be shut down and all the staff be fired. He thought this would give the animators a sense of the consequences of failure and make them better artists if and when they were re-hired for the next film. No one was ever sure if he was just kidding.

Fun workplace! More here.

Thanks for reading! This newsletter is free, but if you’re feeling generous you can support my work by ordering my Daily Rituals books from Bookshop or (if you must) Amazon.

I’m so grateful for your summary of the doc Mason! I feel like he could benefit from the love and compassion of a 12step program. In my humble opinion, the creative process doesn’t have to be selfish or result in the abuse (his son!) of other creators. Ultimately, creativity is a selfless act. It’s a gift we offer to the Creation. I know lots of generous, kind and incredible creators who don’t abuse themselves or others to get their wonderful work done. I feel like this doc will continue to perpetuate the myth that the artists must be tortured to create great work. That’s kind of a bummer- or maybe the youth will see the folly in his example? I hope so! We all deserve to be joyful.

P.S. It was a little reminiscent of Jiro My Dream of Sushi- with the terribly sad father son dynamic. I’m not well versed in Japanese male culture.

Maybe it's not actually selfish to choose to art-making over other uses of life energy — for many artists it might be better described as a stubborn devotion to their innate calling. But some degree of refusing the demands of others HAS TO BE a characteristic of any successful artist — by successful, I mean an artist who actually produces work, more or less steadily. Lacking that devotion, the world (the human part of it) would happily suck away your days, one demand after another, until there's no time or energy left for art-making.