“From rage to despair and back again”

Jean Rhys on writing her masterpiece, the novel Wide Sargasso Sea

Well, Covid finally got me. A mild case, fortunately, but it’s taken longer than I expected to reacquire a normal level of energy and brainpower. (I’m now on day ten—or is it eleven?) As a result, I wasn’t able to write a new issue of this newsletter. Instead, here’s one of my favorite entries from my second Daily Rituals book, on the British novelist Jean Rhys.

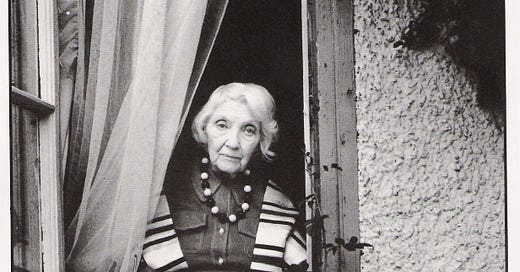

Jean Rhys (1890–1979)

In 1957, the BBC was preparing a radio adaptation of Rhys’s 1939 novel Good Morning, Midnight, and it placed an advertisement asking for anyone with knowledge of the author’s whereabouts to get in touch. At the time, Rhys hadn’t published anything in almost two decades, and many of her acquaintances had lost track of her and assumed that she had died of suicide or alcoholism—believable ends for the Dominica-born author, who seemed to have a gift for self-destructive behavior, and who had spent much of her twenties and thirties destitute and depressed, reeling from one doomed relationship to the next, self-medicating with alcohol. But the BBC advertisement did turn up news—Rhys herself wrote back. She was living with her third husband in Cornwall, and not only was she alive, she was working on a new novel. She soon signed a contract for the book, telling her editors that she expected to be done with it in six to nine months.

In fact, it took Rhys nine years to finish the book, Wide Sargasso Sea, now considered her masterpiece and one of the best novels of the twentieth century. The writing took so long, in part, because Rhys was a perfectionist who reworked the novel over and over until it met her exacting standards—and also because she was spectacularly inept at managing her day-to-day life and was almost continually derailed from the project. As one of her editors, Diana Athill, wrote, “Her inability to cope with life’s practicalities went beyond anything I ever saw in anyone generally taken to be sane.”