Niki de Saint Phalle’s secret jealous lover (her work)

"He is tall, elegant, and like Count Dracula wears a black cloak."

Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers. If someone forwarded this email to you, get your own copy here:

Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002)

Last week, I admitted to feeling jealous of my New York friends who are able to go see the Alice Neel retrospective now on view at the Met. This week, I thought I’d continue the theme: I’m also jealous of folks getting to see the Niki de Saint Phalle retrospective now on view at PS1!

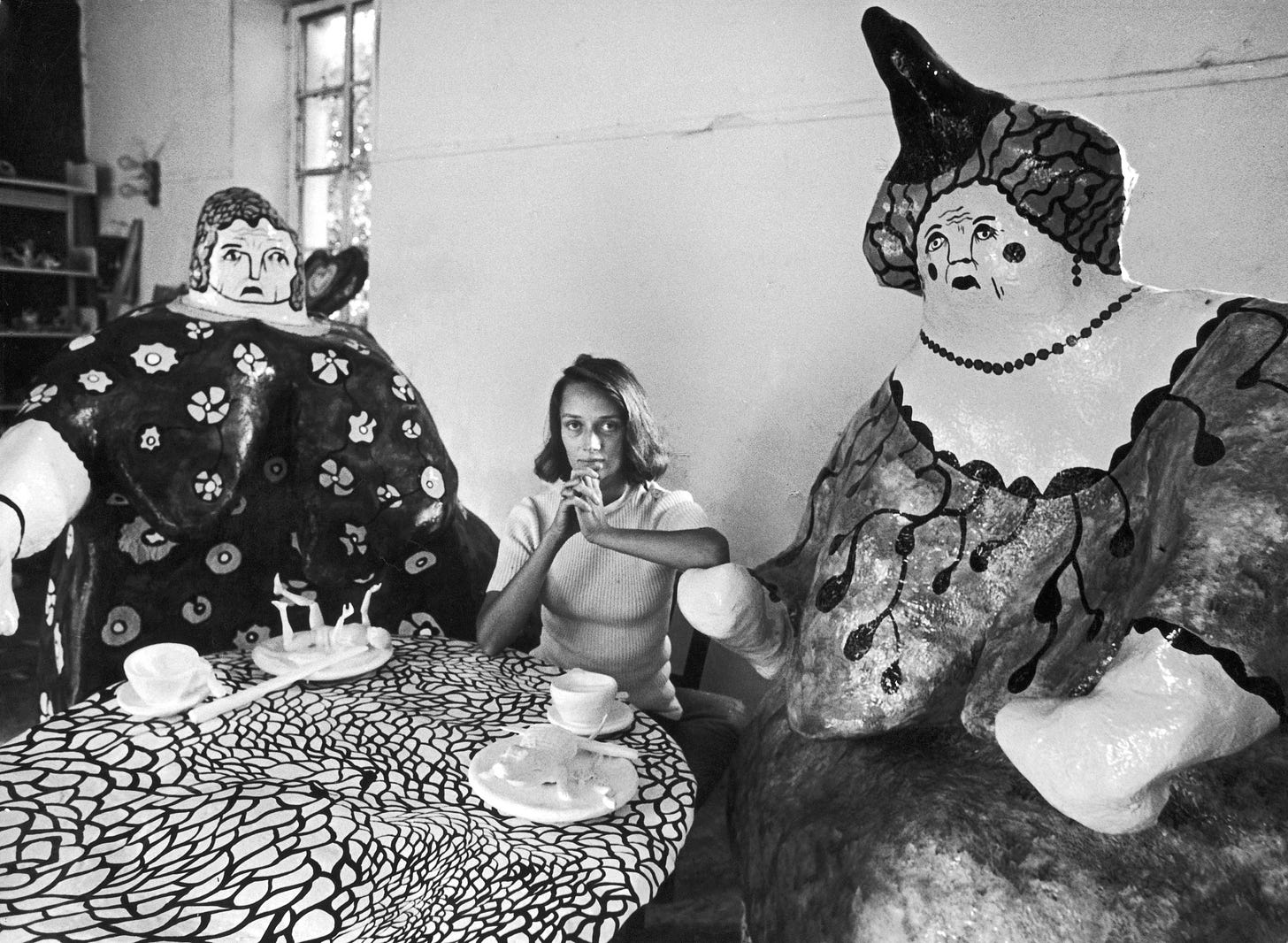

Like Neel’s portraits, Saint Phalle’s sculptures exhibit an exuberance and a larger-than-life quality that seem appropriate to this moment of reemergence. Though she first gained notice for her “shooting paintings” (see video below), and then worked primarily in sculpture, Saint Phalle gradually expanded her practice to create, in the words of the PS1 curators, “charged spaces of imagination from which she envisioned experimental societies emerging, places ‘where you could have a new kind of life, to just be free.’”

That last quote strikes me as a beautiful sentiment for a season in which many of us are returning to quasi-normalcy, with joy and relief and gratitude—but, at the same time, finding the old normalcy to be as limiting and problematic as ever.

Born near Paris, Saint Phalle spent most of her childhood on New York’s Upper East Side, which sounds luxurious but was, in fact, hellish: Saint Phalle’s mother was physically violent and her father sexually abused her for years. As a teenager, she began working as a model, appearing on the cover of Life at 18. At the same age, she married Harry Mathews; over the next few years, he would study music at Harvard and then commit to writing, she would take up painting, and they would have two children and move the family to Paris. In the second book of Saint Phalle’s two-volume autobiography, there’s a charming passage describing their lifestyle as new arrivals in the City of Light: