Rip it up and start again

A bold strategy for second drafts—plus, MITZ on Sunday

HNY! In the spirit of new beginnings, here’s a clever and somewhat outlandish strategy for making your writing feel fresh—though I think it could be adapted for any kind of creative work, not just writing—that I read about last month in Bec Evans and Chris Smith’s terrific newsletter Breakthroughs & Blocks.

It comes from the bestselling author Oliver Burkeman, who says that his favored method for writing something new—whether it’s a newsletter issue or part of a book chapter—is to get a draft going on the computer, print it out, delete the version on-screen in front of him (!), and then retype it from the printout.

As he’s retyping, Burkeman inevitably makes changes—and these changes, he says, “come very easily and naturally,” much more so than if he were to just fiddle with the draft on-screen. He continues:

I know this strikes some people as an arduous idea, but to me it’s the exact opposite, right? It’s like: I’ve written this thing, I’m not happy with it yet. I print it out, I type back in. Typing it back in is just admin work, right? It doesn’t tax my soul in some terrible pretentious writer way. It’s just typing it back in.

Right around the time I read about Burkeman’s write-print-delete-retype method, I stumbled across a video of the filmmaker Taika Waititi recommending this same technique for screenplays—except Waititi takes it a step further.

He says:

What I do—and nobody ever, ever takes this advice, but—I usually write the script, write one or two drafts, then I will put it away for a bit, maybe a year. Come back to it, and I’ll re-read it, maybe once or twice, and then I will throw it away. Well, maybe make one copy, put that on a little USB stick, and then I’ll lock it away somewhere. And then I’ll rewrite the whole thing from memory, from what I’ve read. And what I think is useful about that is you filter out all the stuff that doesn’t seem very important. So what happens is your 120-page script suddenly become 70 pages. And it’s just the bare bones, the very slim, sleek structure of your film. And that’s when you can start putting in more jokes or, like, the tonal stuff that makes it your own thing.

I haven’t tried this—and I don’t know if it would work as well for nonfiction books—but I find the idea very persuasive: that by rewriting your draft from memory, you get the distilled essence of the material and jettison all the extraneous stuff.

Since these things tend to come in threes: After watching the above clip, I almost immediately discovered another example of this method, via a link shared by one of my Worm Zoom participants on the tracking spreadsheet we use to chart our daily progress (hi, Kelly!). It’s from a 2023 New York Times profile of the novelist Lauren Groff:

When Groff starts something new, she writes it out longhand in large spiral notebooks. After she completes a first draft, she puts it in a bankers box—and never reads it again. Then she’ll start the book over, still in longhand, working from memory. The idea is that this way, only the best, most vital bits survive.

“It’s not even the words on the page that accumulate, because I never look at them again, really, but the ideas and the characters start to take on gravity and density,” she said.

“Nothing matters except for these lightning bolts that I’ve discovered,” she continued, “the images that are happening, the sounds that are happening, that feel alive. Those are the only things that really matter from draft to draft.”

The NYT profile also says that Groff works on several projects at once, and that she keeps the projects in different corners of her office, so that switching among projects means physically moving from one end of her desk to the other, or from the desk to a daybed. (Note to self: buy a daybed.) “I’m trying to Jedi-mind trick myself into not putting so much pressure on any particular project by having them be really loose for the first really long span of time,” Groff says. Yes! I love the that idea that writing—or making anything—is Jedi-mind tricking ourselves; it really is. And that it’s also a game of pressure: of putting the right amount of pressure on a project (often, not too much) for the right amount of time (the longer the better?) and then seeing what weird diamond emerges from the rubble.

MITZ ON SUNDAY

Reminder: The second meeting of the Subtle Maneuvers Book Club takes place this Sunday, January 11th, at 11am Pacific / 2pm Eastern / 7pm UK time. We will be discussing Sigrid Nunez’s 1998 novella Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury. I love this book! It’s about Virginia and Leonard Woolf, the Bloomsbury Group, the joy and agony of writing, the soulfulness and mystery of animals, and plenty more. (If you haven’t had time to read it, it’s not too late: Mitz comes in at less than 150 pages in paperback; you could probably start and finish it in a couple hours.) I’m really looking forward to discussing it with you all on Sunday—find the full details and the Zoom link here:

Note: Book club meetings are for paid subscribers only—but if you want to take part and really can’t afford it at this time, just reply to this email and I’ll add you to the comp list, no questions asked.

RELATED ISSUES

From the archive:

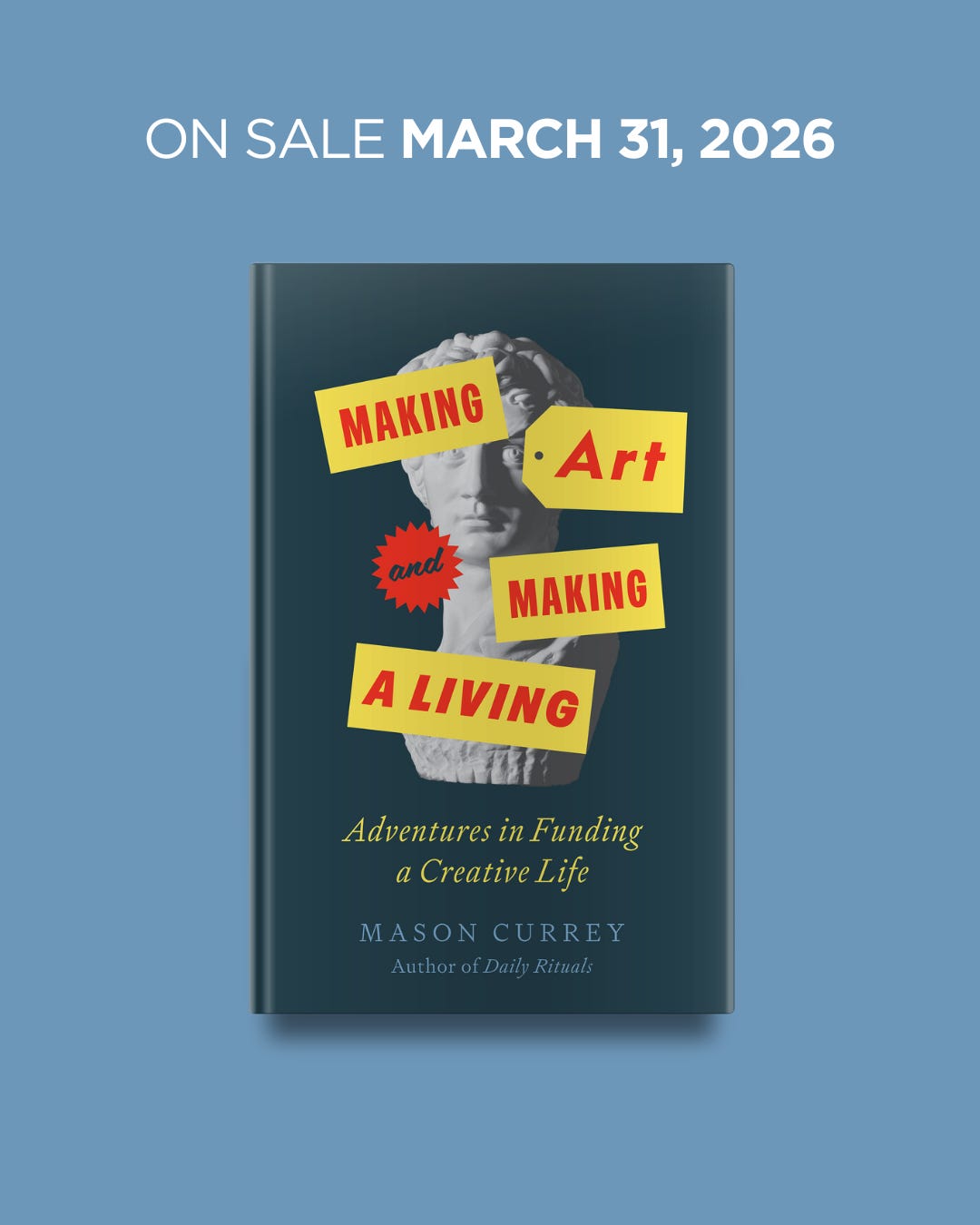

Thanks for reading! This newsletter comes out every other Tuesday , and you can help keep it coming by upgrading to a paid subscription, pre-ordering my next book, forwarding this email to a friend, or even just clicking the “like” button below. 🙏

This reminds me of the unintended experiences I used to have working in local government, where all the computers were too old to cope and crashed all the time, throwing away whatever work you had done. My colleagues and I would mutter “well at least it’s easier on the third attempt” - and it was!

Maybe an easier approach to this would be simply writing by hand. It works wonders for me, because it forces me to edit the whole thing as I type the manuscript.