Sculptor Anne Truitt’s retreat routine

Plus: Advice on doing the hardest thing first so you can't avoid it later

Welcome to the fourth issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Though this newsletter suddenly feels rather frivolous in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, I plan to continue it in the hope that some of you will still find it relevant and/or a welcome break from more serious news. In the meantime, please stay safe—and do your best to practice social distancing—during this anxious moment.

Anne Truitt (1921–2004)

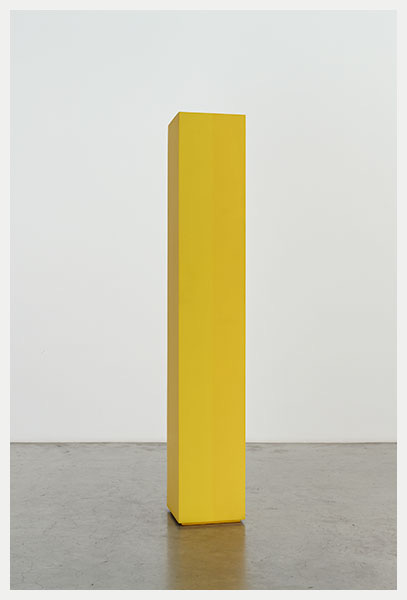

The American sculptor—who would have turned 99 today—is remembered for her hand-built and hand-painted wooden columns, which she painstakingly coated with acrylic, then sanded down, then re-coated and sanded again, repeating the process for weeks or months until she had created an object that, in her words, was “not subject to time but illuminated by it.”

But Truitt is also remembered for her trilogy of published journals, starting with 1982’s Daybook, in which she reflected on her daily life as an artist, a wife, and a mother. As Truitt wrote, her work as a sculptor “suddenly erupted into certainty” when she was 40 years old, living in Washington, D.C., with her husband and their three young children, working in her backyard studio during whatever time should could steal away from her domestic obligations. To her friends and neighbors, she wrote, “I had rarely let on that I was doing anything beyond being a housewife.”

Because of this, Truitt relished those times later in her career when she was able to single-mindedly focus on her work. In Daybook, she described her daily routine in the summer of 1974, when she was staying at Yaddo, the storied artists’ colony in Saratoga Springs, New York: