Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Previously: an end-of-summer mega advice column.

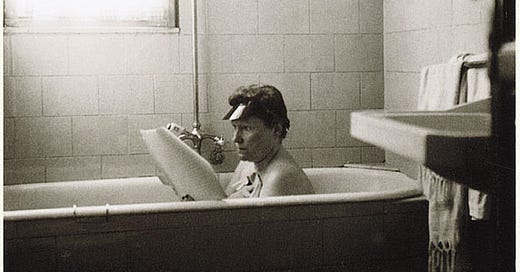

Sybille Bedford (1911–2006)

Those of us who have a hard time keeping up our creative work on a regular basis tend to draw on a catalog of familiar excuses: If a day job isn’t draining our time and energy, then it’s the noisy neighbors, or the lack of a proper work space, or the deliriously worrying state of the world, or some other force beyond our control. So I was tickled recently to read the German-born English writer Sybille Bedford’s explanation for her modest literary output, which she described in her 2005 autobiography: “great natural sloth.”

Ha! Maybe that’s a larger component of my own inconsistent productivity than I would like to admit—though, in fairness to Bedford, it wasn’t the only reason for her years of not writing. At another point in her autobiography—titled Quicksands, it was published when Bedford was 94—she elaborated on the factors behind the “long fragments of the life I wasted in not working”:

Oh what has remained undone by sloth, discouragement, and of course distractions . . . Distractions of living the siren song of the daily round—chance, often choice led me to spend the squandered years in beautiful or interesting places: to learn, to see, to travel, to walk in nocturnal streets, swim in warm seas, make friends and keep them, eat on trellised terraces, drink wine under summer leaves, to hear the song of tree-frog and cicada, to fall in love . . . (Often. Too often.)

Now those are good excuses for not writing! In all seriousness, though, a sympathetic reader can’t help but suspect that what Bedford did write would not have been nearly as magnetic if it hadn’t been for her travels, her friendships, her affairs, and her leisurely late-night meals on trellised terraces under summer leaves. (God, that sounds lovely.)

Bedford lamented the years she “wasted in not working,” but the truth is that there were a lot of years when she did work steadily, starting in her early 40s. That’s when she wrote her first book, a sort-of travelogue based on a year in Mexico, and her first novel, A Legacy, published three years later. In Quicksands, Bedford described the conditions that finally did get her to work in a regular way. To begin with, there was a phenomenal act of generosity from a friend who “made over a part of her income for me for three years” so that Bedford could get on with her stalled Mexican travelogue. (As a New York Times headline writer once put it, Bedford was “a world-class writer and a world-class freeloader.”) On top of that, she lucked into a living situation that proved ideal: Two friends living in Rome wanted to sublet their flat, and their landlady—“aged, hostile, hard”—wouldn’t let them go unless they found a reliable, quiet replacement.

Bedford went to look at the place. The rent was cheap; the location, excellent. The only catch was that the flat was on the roof of the building, and it was really more like a hut, “a longish kind of shed cobbled together, it would seem, from tarred paper and packing-case wood.” But the interior was not bad—it had a marble bathtub—and the surrounding rooftop was a charming “profusion of tangled greenery struggling out of a variety of semi-broken tubs and urns.” So Bedford took the place, and after some help from friends fixing it up, she finally found the daily writing rhythm she had long lacked: