Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Previously: Arthur Schopenhauer, Germany’s routine-loving, flute-practicing philosopher of pessimism.

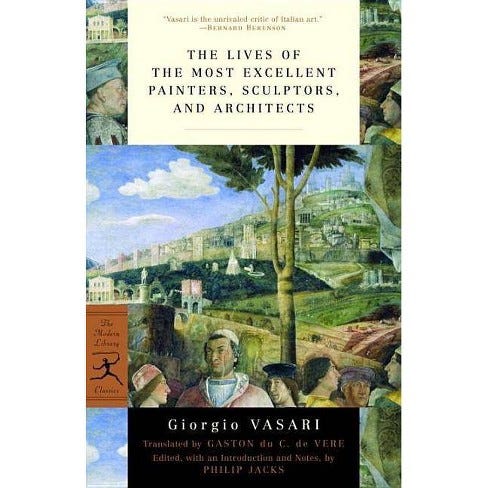

For my new book project—which I should be able to announce very soon, I swear!—I recently finished working my way through Giorgio Vasari’s 1568 Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, the prototype for artist biography in the Western tradition—and a genuinely rollicking read, stuffed with vivid anecdotes about the trials and tribulations (and triumphs) of the Renaissance masters, written in a loquacious, hyperbolic, and occasionally almost breathless prose style that (at least in its English translation) I found utterly charming.

For this issue of the newsletter, I thought I would pull out a few aspects of Vasari’s Lives that struck me as quite relatable to contemporary creative workers. Even 470 years later, some things about the art life have barely changed.

ARTIST–CLIENT NEGOTIATIONS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN FRAUGHT

And they were especially fraught at this moment, when painters and sculptors were trying to establish themselves as deserving of greater respect and higher social status than mere artisans. As a result, stingy buyers were particularly offensive figures who had to be dealt with harshly.

The sculptor Donatello, for instance, once received a commission from a Genoese merchant to make a life-size bronze bust. When the merchant came to see it, Vasari writes, “it appeared to him that [Donatello] was asking too much.” Donatello’s patron, Cosimo de’ Medici, tried to intercede in the price dispute, but when the merchant dared suggest to Donatello that he had only spent a month on the statue and could not expect such a high day rate, Donatello pushed the statue out the window and “sent it flying straightway into the street below, where it broke into a thousand pieces.”

Seeing the bust shatter, the merchant immediately regretted his stinginess and offered to give Donatello double the price to remake it, but the sculptor refused. The insult to his dignity had been too great and no amount of money or entreaties could convince him to make another work for the merchant from Genoa.

BEING BETTER THAN YOUR PEERS HAS ITS DRAWBACKS

The Lives are stuffed with stories of artists distinguishing themselves with their superior talent—only to attract the envy and malice of their peers. That undoubtedly happens nowadays, too, but in 15th-century Tuscany the consequences could be dire: Career sabotage was rampant, and physical violence was not uncommon. When the supremely gifted painter Masaccio died suddenly at the age of 26, people suspected that he may have been poisoned by envious fellow painters. And when Michelangelo was a young apprentice, one of his fellow pupils was so “moved by envy at seeing him more honored than himself and more able in art,” Vasari writes, that this jealous pupil “struck him a blow of the fist on the nose with such force, that he broke and crushed it very grievously and marked him for life.”

A VERVE FOR SELF-PROMOTION WAS A MAJOR ASSET, THEN AS NOW

Irritated that today’s artists are expected to maintain bustling social media presences on top of, you know, actually making quality work? Alas, it has always been so. Sure, social media is new—but throughout history the most successful artists have tended to be zealous and canny managers of their public profiles, and the Renaissance was no exception.