Wayne Thiebaud on finding “charm and freedom” in your work

The late American painter on a delicious artistic breakthrough

Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers, which I launched two years ago this week. Thank you all for reading, commenting, and sharing, your enthusiasm keep this newsletter going!

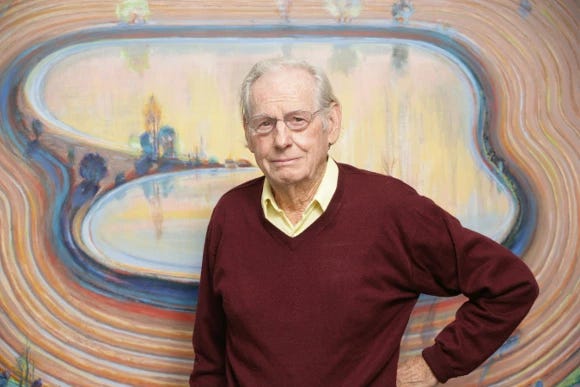

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–2021)

The California-based painter died last Christmas at age 101. Though I’ve only seen his paintings in person once—at an SFMOMA exhibition in 2018—Thiebaud’s glowing pastel cakes, pies, hot dogs, ice-cream cones, and other lovingly rendered foodstuffs gave me a kind of giddy feeling, and I was glad last week to finally find some time to delve into his life and work.

About those pies and cakes: Thiebaud explained how he arrived at his most famous subject matter many times. In the 1950s, he took a year off from teaching art in California—and from feeling stuck with his own painting, which he was doing on the side—to go to New York and hang out with his artist heroes, among them Willem de Kooning, who was friendly to Thiebaud and told him to make sure to paint “something that you feel is real.” When Thiebaud came back to California, he decided to strip away all the “mannerisms” of his existing work, and “just try to get a composition as basic as I can.” He asked himself:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Subtle Maneuvers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.