A master class in creative doubt

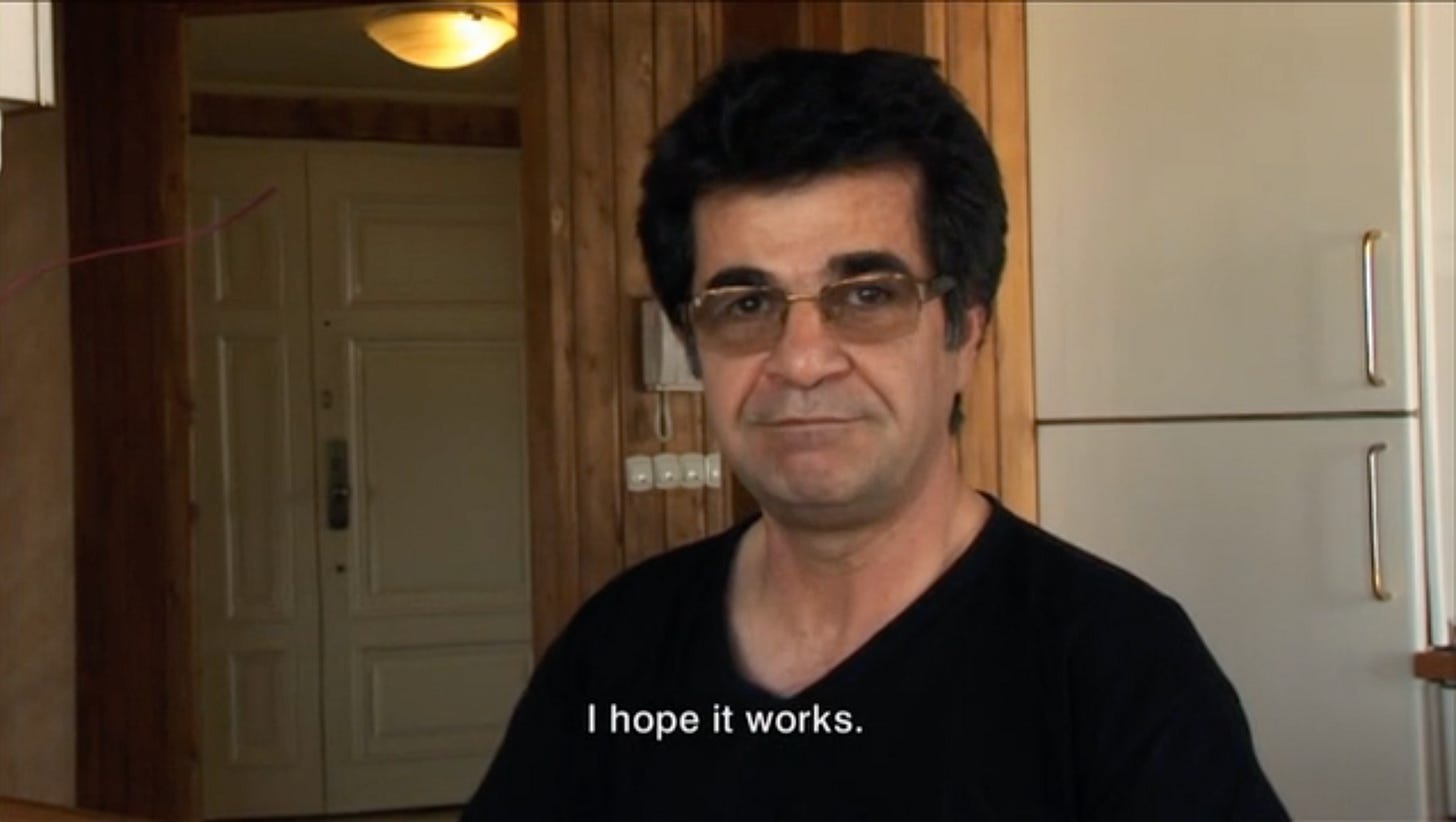

And what to do with it, featuring the Iranian director Jafar Panahi

Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers, my fortnightly newsletter on wriggling through a creative life. Previously: some motivational advice from Jonah Hill’s therapist.

Jafar Panahi (b. 1960)

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you’ll know that I have a tendency to dwell on the more frustrating aspects of the creative process. Because it is frustrating! But I also want and need reminders that creating things is not only a slog, that at its best it can be an engrossing puzzle that demands all your resources but does not exhaust them.

I had just such a reminder last week while watching the Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s 2011 documentary This Is Not a Film. You may be familiar with Panahi’s name—his latest film, No Bears, has been getting extremely positive reviews and is now in limited theatrical release in the United States. Panahi managed to make the film despite an Iranian government ban handed down in 2010, which barred him from filmmaking, screenwriting, traveling abroad, or giving interviews for twenty years.

In fact, No Bears is the fourth feature that Panahi has managed to make despite the ban. The first was This Is Not a Film, which Panahi shot shortly after the 2010 verdict, while he and his lawyer were appealing the decision. Stuck at home and unable to work, Panahi starts recording his daily routine in the Tehran apartment he shares with his wife and children, who are away visiting family. He putters around, makes calls, waters the plants on the balcony, and tries to get his daughter’s pet iguana, Iggy, to eat something.

Then he gets an idea. If he’s not able to make what he hoped would be his next film, what if he instead read the screenplay on camera and explained how the film would look, what the effect would be? With the help of a friend who acts as his cameraman, Panahi starts describing the film’s setting—a girl’s bedroom—and marking out its dimensions with masking tape on his living-room rug.

What follows is one of the best depictions of the creative process I’ve ever seen. We get to watch Panahi, in real time, try to conjure the images he had hoped to film, using only the humblest household props. We see his surge of enthusiasm as he explains the story—and we also see this enthusiasm abruptly run out. No, he decides, this exercise is worthless, a lie. But then, delightfully, we see him head to his entertainment center and start playing DVDs of his previous films, to explain why this screenplay-reading is not at all the same thing as a finished film, and to unpack how some of the key scenes in those films were realized.

Suddenly we are getting a miniature master-class in filmmaking, or really in making anything. Revived by this exercise—though at the same time still convinced that what he’s doing is a lie—Panahi keeps soldiering on with the non-film we are watching, which soon veers in another direction—and which we are only able to watch because it was smuggled out of Iran on a flash drive concealed in a birthday cake.

For me, this section of the movie was electrifying. When I run into major doubts with my work in progress, I have a tendency to freeze up, to become paralyzed, and all too often to default to avoidant behaviors. Here was Panahi showing the opposite approach, and the only proper response to the pervasive uncertainty of any creative practice. This is the goal: to be 100 percent in doubt about what you’re doing and 100 percent still doing it.

PANAHI IN PRISON

When the Iranian government banned Panahi from filmmaking, in 2010, it also sentenced him to six years in prison, but then did not enforce the prison sentence. Tragically, that sentence is now being enforced. Since last July, the 62-year-old director has been serving his six-year term in the notorious Evin Prison. You can read more details in this October interview with his son, who, thankfully, reports that Panahi is doing OK:

Jafar is in the public unit and calls every day, and we meet him in person once a week.… He has made a lot of friends in prison, all of whom are honest and straightforward fellow Iranians, including doctors, engineers, writers, directors and poets, as well as top-rank university admittees and environmental activists. Overall, whoever is concerned about Iran is in prison.… The nice thing about prison for Jafar is that now he has been forced to exercise and read more to pass the time.

As his son says, Panahi’s imprisonment is part of a larger crackdown on dissent in Iran, which intensified in the wake of the nationwide protests that erupted last fall following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini. Here’s a list of ways to support the protestors in Iran. If anyone reading has suggestions for organizations to follow or other ways to help, please leave them in the comments section below.

HOW TO WATCH PANAHI’S FILMS

From the New York Times, a good guide on which of Panahi’s films are available to stream. I watched This Is Not a Film on Kanopy, which I had somehow never used before. You just input your public-library card number—or, if you’re a student or professor, your university ID card number—to gain access to a huge library of films to stream, for free.

I also really enjoyed Panahi’s contribution to the 2021 Hulu documentary The Year of the Everlasting Storm, for which seven international filmmakers contributed short works made in Covid lockdown. Panahi’s piece (the first one) is a mini-sequel to This Is Not a Film, once again filmed in his Tehran apartment and once again featuring the irrepressible Iggy.

Thanks for reading. This newsletter comes out every other Monday—and you can help keep it coming by becoming a paid subscriber, buying one of my Daily Rituals books, forwarding the newsletter to a friend, or even just clicking the “like” button below.

"This is the goal: to be 100 percent in doubt about what you’re doing and 100 percent still doing it."

Very inspiring words for me at this moment, as I work on a new recording. Thank you.

Mason, I so appreciate you drawing attention to Panahi's situation and the broader political situation in Iran! Most people read this film as (only) a statement on Iran's censorship of filmmakers, so I really like this analysis of it through the creative process. If you haven't seen THE MIRROR, check that out. I think it's his best film.