Jane Bowles was vulnerable and strong

“I’ve got to do it my way and my way is more difficult than yours.”

Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers, which I started writing four years ago this week. Thank you all for reading along! This has been my favorite writing I’ve ever produced, even as it’s also been the least remunerative. (Isn’t that always the way?) If you’d like to show your support and help me prioritize this work going forward, your paid subscriptions sincerely make a huge difference—THANK YOU.

Special thanks to my book club for getting me to read Jane Bowles’s strange and hypnotic novel Two Serious Ladies last month, which inspired today’s post.

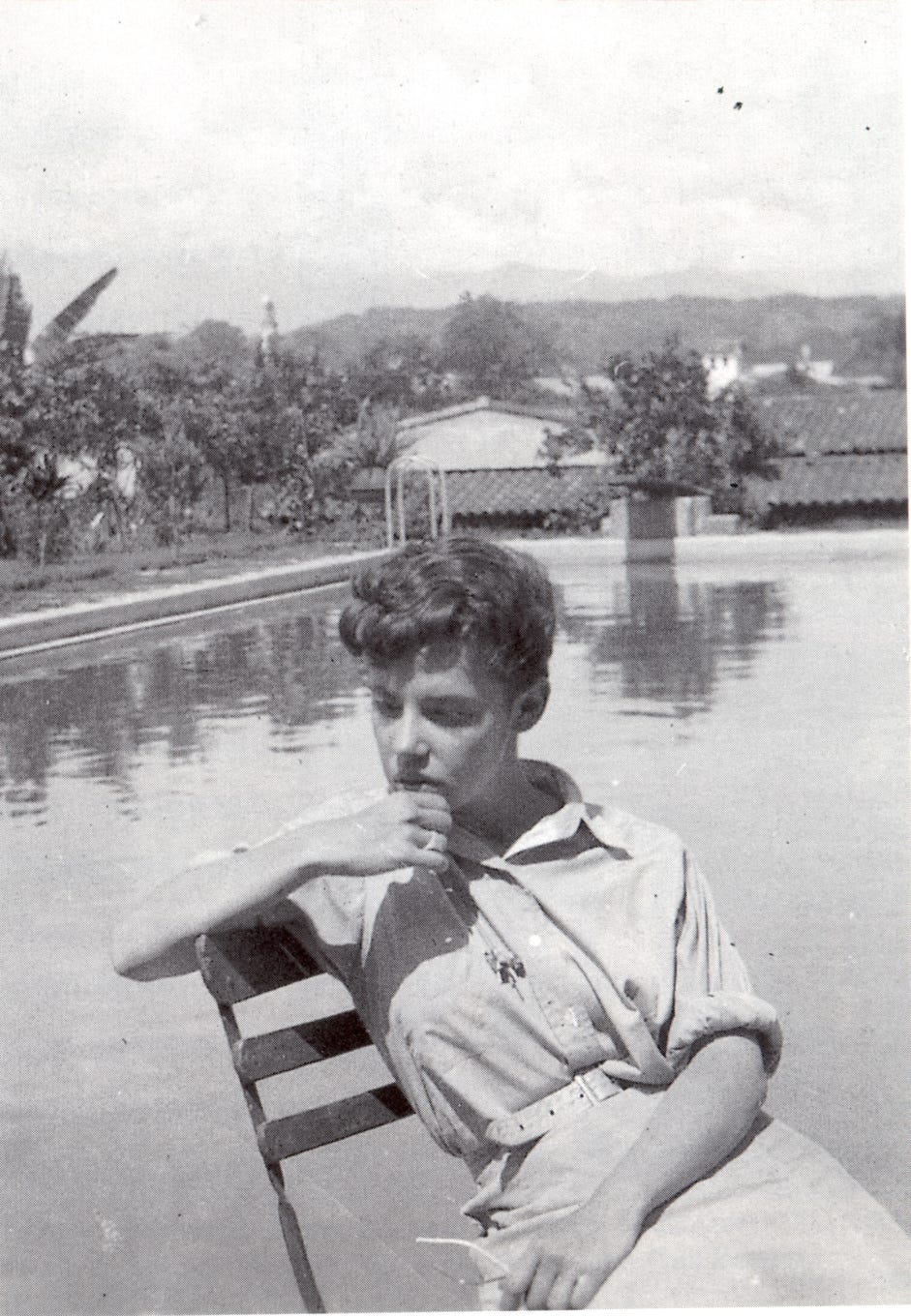

Jane Bowles (1917–1973)

When writing feels impossible, my favorite thing to do is to read about other writers for whom it was even more impossible—and was writing ever more impossible for anyone than it was for Jane Bowles?

She produced a novel, Two Serious Ladies, in 1943, when she was 24 years old. Then a play, In the Summer House, in 1953. Other than that, there were a handful of short stories. Despite years of trying, she never finished another novel. “My slowness is appalling and the number of hours when I simply lie on the bed without reading or thinking would shock you,” Jane wrote to her husband, Paul Bowles, in August 1947, while working on the second novel she would never complete. Later in the same letter, she continued:

To give you an idea of my slow pace—I have done about thirty-three typewritten pages in the same number of days. One day I do three pages but then the next I do nothing—possibly—and this is working all day and after dinner! I mean going at it and stopping for a while and then going at it again. Of course I do a great deal of thinking which takes me forever because my mind is apt to wander—every twenty minutes if I have reached an impasse or a complicated thought and then I am apt to dream the whole morning about some flirtation.

These flirtations were a consistent feature of Jane’s life, and they often led to more complicated romantic entanglements, which inevitably took away from her writing. (Though married, she and Paul lived apart for long stretches and both took other lovers, while remaining each other’s life-long confidantes and supporters.)

Her drinking didn’t help either, nor did the frequent chaos of her daily life. The harpsichordist Sylvia Marlowe said of Jane:

She fussed a lot about her work, but she really didn’t spend the kind of time working that most artists have to spend. She was self-indulgent and spoiled. She had no routine, and she got almost no sleep.

The painter Maurice Grosser observed Bowles’s writing habits in the summers of 1944 and 1945, when he stayed with her and her lover in Vermont:

In the morning she’d come down to a rather late breakfast. She was often in a bad temper in the morning. She’d have her breakfast, which consisted of two eggs, fried so they were burned on the outside. She loved to have the whites crinkled and scorched. Then she took a canteen of water and a notebook and a pillow and she went out under a distant tree and she’d stay there all morning. But if it rained, she’d come back, leaving the notebook and the pillow lying under the tree.

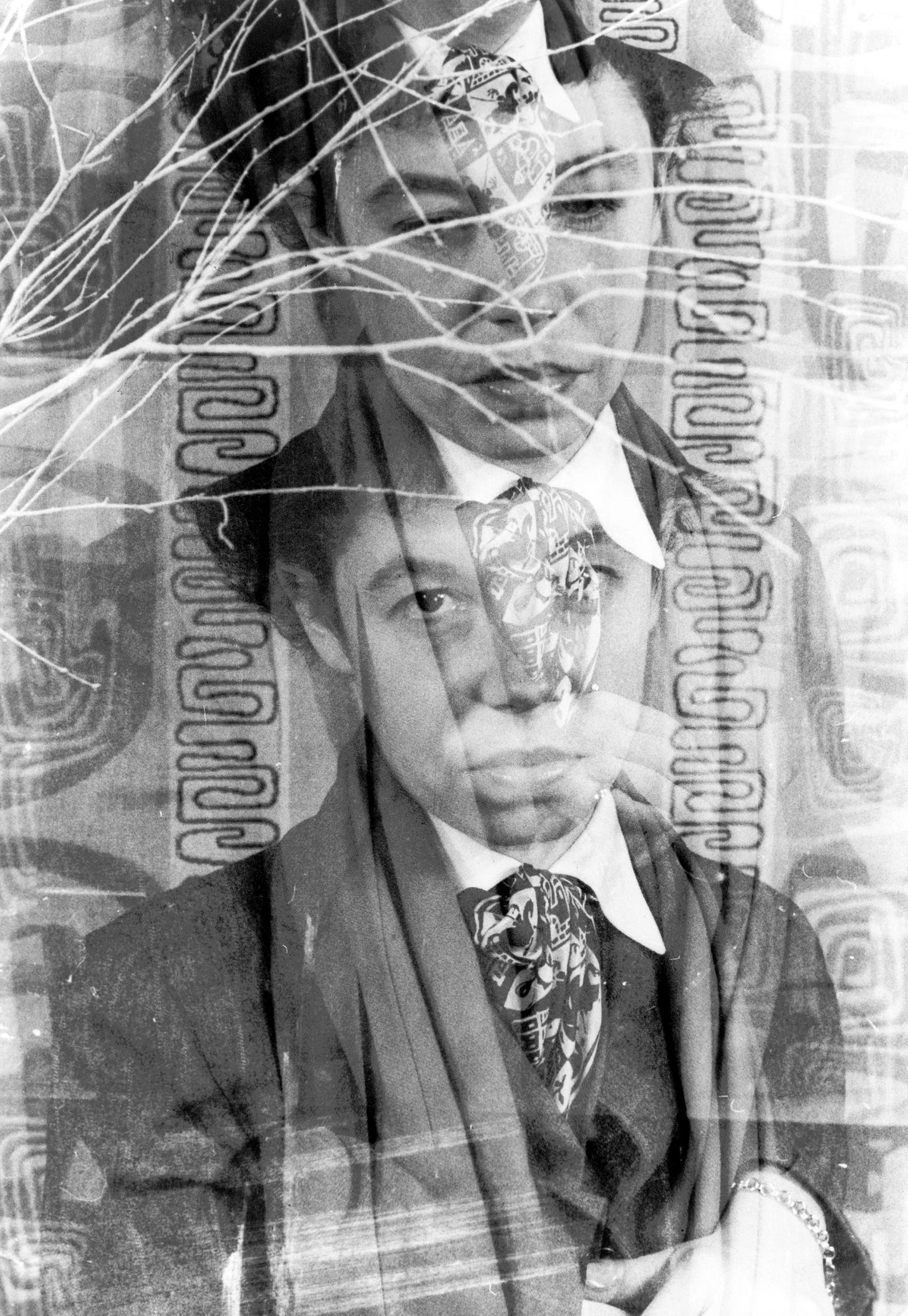

“I am so slow it is almost as though I were going backwards,” Jane wrote to Paul. But her difficulties weren’t just a matter of poor discipline or inconsistent work habits. Bowles absolutely refused to repeat herself as a writer, and so each new project required an almost total reinvention. “What she wanted to do was more than she could do, more than perhaps anyone could do,” Paul told the biographer Millicent Dillon.

She never had the sense that she had a body of work behind her. It was as if each new work she began was from scratch. She refused to pay any attention to what had gone on during the writing of Two Serious Ladies. That was one thing, that was finished, she said. This had to be entirely different, with a different style, a different subject matter.

Paul would argue for her to take a simpler approach, and Jane would say: “No, no, no. That’s your way, not my way. I’ve got to do it my way and my way is more difficult than yours.”1 Paul would reply: “But why do you want it to be so difficult?” But for Jane—according to Paul—“it had to be difficult from the first paragraph in order for her to have respect for it.” He said:

She wasn’t interested in making it easier. When she finished a thing, she wanted to be able to say she’d done it all herself. She had to make everything herself. She couldn’t use the hammer and the nails that were there. She had to manufacture her own hammer and all the nails.

But it was more than that, too. Jane didn’t just need to reinvent her means of expression; she had to get to the bottom of things in her actual lived life, even if she couldn’t quite articulate what that meant. In Claire Messud’s introduction to my paperback edition of Two Serious Ladies, she quotes a friend of Jane’s who said: “Jane was vulnerable and strong. She was always testing herself and she kept on testing to see how it would come out if she put herself in danger.”

This danger was literal. Messud repeats a story from Paul, about a night early in their marriage when Jane stayed out late without him and finally returned home the next morning, barefoot. When Paul asked where she’d been all night,

She’d answer that she’d been wandering around the docks all by herself at four or five in the morning.

“Why?”

“Because that was the one place I didn’t want to be. I’m terrified of it.”

“Then, Jane, why did you go?”

“Don’t ask me. You ought to know why. I had to or I couldn’t face myself in the mirror tomorrow if I hadn’t gone because that was the one thing I was afraid of.”

There’s a lesson in here somewhere. Is it that making art is always somehow tied up with overcoming fear? Or maybe not overcoming it—maybe just tolerating it, or accepting it, or even celebrating it? “Happy to find myself as uncomfortable, shy and insecure as ever,” Jane wrote to a friend in 1949, and I like to think that she meant it.

RELATED ISSUES

From the archive:

TWO VOICES, ONE AND TWO

Did anyone try out the David Milch writing exercise that I shared last time? The idea was to write a dialogue between two voices, without any pre-planning, without identifying or naming the voices, and without any description or scene-setting, and to do this in 20-to-50–minute sessions for five days in a row. I followed Milch’s instructions and found the exercise engrossing. As for whether it revealed the “true categories” of my imagination, as Milch said it would—well, the biggest thing I noticed was that my dialogues tended to involve one voice trying to get the other voice to understand something. There was a consistent beseeching tone—which, hmm, maybe that is the true category of my imagination? I do feel like I’m always pleading my case in some weird way. Curious to hear what you all discovered; you can leave a comment below or just reply to this email.

Thanks for reading! This newsletter comes out every other Monday—and you can help keep it coming by upgrading to a paid subscription, buying one of my Daily Rituals books, forwarding this email to a friend, or even just clicking the “like” button below.

Paul’s position was complicated. He had helped Jane revise Two Serious Ladies, and that assistance proved crucial to the book’s completion. But the experience had inspired him to revisit his own writing ambitions—when they married, Paul was a noted composer—and within a few years Paul was becoming a celebrated writer himself. His 1949 novel The Sheltering Sky was a sensation in the literary world. It’s overly simplistic to say that Paul’s success stopped Jane from writing, but it was certainly a factor.

As a writer with ADHD and mental problems, it sounds like Jane possibly had mental health issues and would have faired differently with her writing if she had lived in another time.

Jane’s story is quite painful to read, and knowing she gets a stroke at 40 making it even harder to write! But I love the love story of Paul and Jane Bowles, and his encouragement to keep things easy. It seems to me that Jane was consumed with the myth of complete originality which majorly blocked her work. Making peace with bad art in order to make art at all is my takeaway here.