Welcome to the 99th issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Last time, I wrote that I was planning something special for this 100th issue . . . but it turns out I miscounted, lol. So here’s a normal issue on the German conceptual artist Martin Kippenberger.

In the next issue—the actual 100th!—I’m launching a special three-part series on creative blocks that I’m calling #blocktober. If you, like me, seem to be chronically blocked in your creative life—or, even better, if you’ve solved a longstanding block—please tell me about it over email or in the comments section below; your experiences will help inform my #blocktober dispatches.

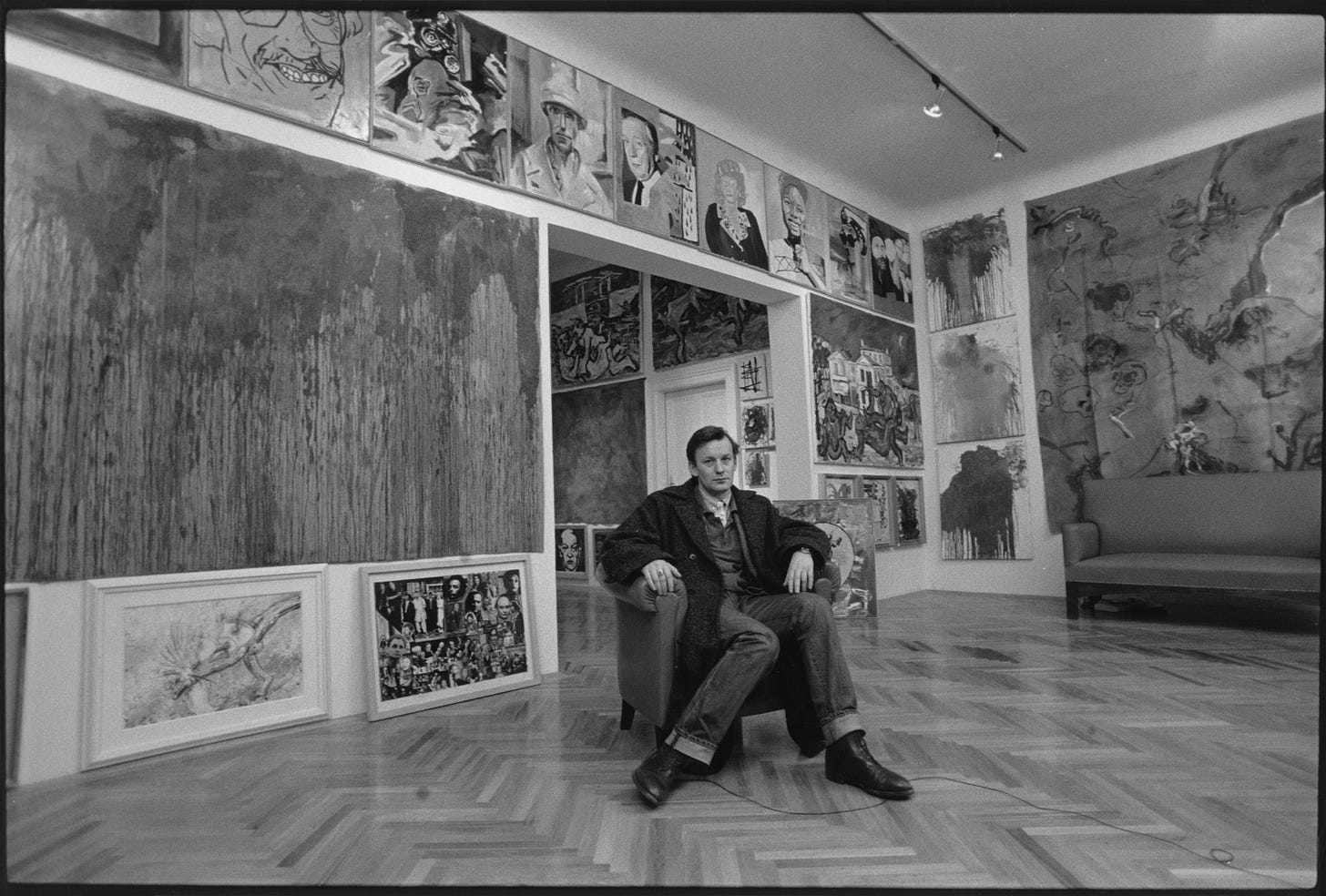

Martin Kippenberger (1953–1997)

The motivating question behind my next book is pretty simple. Becoming a serious writer or artist or musician and paying the bills while doing it is hard—sometimes it seems impossible. How did anyone do it? I mean, really how did they do it?

One answer I keep running across: They did it by being a scoundrel! Martin Kippenberger is an excellent example: The late German artist alternately charmed and wore out everyone he met with his energy, his demands, his debts, his drinking, and his constant improvisatory assault on the project of being an artist. Ultimately, he wore himself out, too, dying of alcohol-related liver disease at 44. In that short time he was astonishingly prolific. His motto was “Think today, done tomorrow”—as soon as he had an idea for a new project, he executed it as fast as possible, often the very next day.