Time, Strength, Cash, Patience

If I tell you about my new book project, then it’s real and I actually have to write it.

Welcome to the 55th issue of Subtle Maneuvers. Previously: the art life has always been a struggle.

When I started this newsletter last year, one of my goals was to give readers some behind-the-scenes peeks of my next book as it gradually comes together. My hope was, and is, to build anticipation for the book, sure—but, more importantly, I wanted to feel accountable to a wider audience than the three people normally privy to my work-in-progress (my wife, my editor, and my agent) and also feel part of a larger community of creative people trying to make ambitious work and finding the process difficult, frustrating, all-consuming, exhilarating, comical, posture-wrecking, and so on.

So I’m excited to finally be able to announce said book project! (Several months later than hoped, but so it goes.) Here’s the announcement that went out last week:

(The weird publishing-industry rite of announcing book deals via a screenshot of the text that appears in a subscriber-only email is a whole other subject.)

Though I’m only now announcing the book, it’s an idea I’ve been mulling over for a long time. I’ve always been fascinated by stories of how writers, artists, and musicians actually funded their creative endeavors (and I named this newsletter Subtle Maneuvers after a Franz Kafka letter in which he complained memorably about his day job.1) Making a whole book of these kinds of stories is something I wasn’t sure would work—but I think I’ve figured out a way to do it that will make for compelling reading and also provide a lot of valuable examples (and cautionary tales) for everyone out there trying to figure out their own path forward vis-à-vis this eternal dilemma of the art life.

The manuscript is due in 13 months! I have a lot to do in that time (A LOT), but at the moment I’m feeling incredibly privileged to be able to delve into this material and report back on what I’ve found. To give you all a little taste of what’s to come, here’s a very small selection of some of the figures I’m excited to write about, from the first few hundred years of my several-hundred-year survey:

Petrarch (1304–1374), who resisted his father’s demands that he become a lawyer (“I couldn’t reconcile myself to making a merchandise of my mind”) in order to write poetry—and who was adept at attracting generous patrons to fund his literary career. Of his first and longest-lasting patron, Cardinal Giovanni Colonna, he wrote: “Serving him was better than living independent, for without him I could never have enjoyed a really free and tranquil life.”

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who, when visiting Venice from his native Nuremberg, marveled at the higher status of artists in Italy, writing to a friend: “Here I am a gentleman, at home a sponger.”

Isabella d’Este (1474–1539), the most astute and determined art collector of the Renaissance, whose refined taste profoundly shaped Western art history—and who never hesitated to harass famous artists whose work she desired.

Titian (1488/90–1576), who routinely set uninspiring commissions aside, neglecting them for months, years, or even decades. The powerful duke of Ferrara was so determined to secure a long-delayed painting that he had one of his ambassadors shadow Titian for more than a year, delivering up-to-the-minute reports on the artist’s activities, health, moods, and the likelihood of the duke’s painting being completed. It was finally delivered 20 months after Titian had promised to begin it “that very morning.”

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), who was one of the most popular and successful artists of his time, and one of the most impressively self-made men in British history. At the height of his popularity he had to set up a virtual portrait-making factory to keep up with the demand, only painting a sitter’s face and head himself and leaving the rest to his army of assistants. William Blake said of him, “His eye is on the many, or rather on the money.”

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), who arrived in Vienna in 1749 a gifted, ambitious young musician—and, in his own words, “had to eke out a wretched existence for eight whole years” before being discovered. Haydn eventually made his way to the court of Prince Nikolaus Esterházy and spent much of the remainder of his career as a court musician at the prince’s remote estate, largely isolated from other composers and trends in music. “I was cut off from the world,” Haydn said; “there was no one to confuse or torment me, and I was forced to become original.”

(I wrote a little something about Haydn’s late-life composing routine last March.)

Hester Thrale (1741–1821), the wife of a wealthy brewer, who was a voracious reader and a lively hostess and who became a close friend and confidant of Samuel Johnson, bringing the depression-prone writer to live in the Thrales’ country estate, where Johnson would pass his happiest years and produce his late masterpiece The Lives of the English Poets. (The idea that Hester and Johnson may have also been involved in a sadomasochistic erotic relationship has invited vigorous debate since it was first proposed by a Johnson scholar in 1949.)

John Mitford (1782–1831), a British naval officer who, after his discharge, “took to journalism and strong drink,” in the words of one biographer. His Grub Street publisher paid him a shilling a day, “which Mitford expended on two pennyworth of bread and cheese and an onion, and the balance on gin.” Since that did not leave anything for rent, Mitford lodged in an old gravel pit in Battersea Fields, where he retired each day with a fresh supply of paper and ink from his publisher, returning the next morning to exchange his day’s pages for another shilling and begin the cycle all over again.

George Sand (1804–1876), who produced a minimum of 20 manuscript pages nearly every night of her adult life, ultimately publishing more than 90 novels as well as scores of novellas, plays, and other works. She wrote for two reasons, she said: “It brings me money and consumes much of the time that I would otherwise spend in the ‘spleen’ to which my bilious temperament inclines me.”

Pauline Viardot (1821–1910), who was born into a family of itinerant singers and became one of the most sought-after opera singers of her age, as well as a canny and enterprising businesswoman. In the words of one historian, “she was extremely skillful in her exploitation of the new economy and, as a woman, unusually independent for this patriarchal age.”

If you made it this far, I’d love to hear what you think of the new book idea and/or my chances of completing the manuscript by May 2022! (Eep.) Even better, if you have any favorite books on the subject, or favorite anecdotes regarding artists’ financial misadventures, please do share them in the comments section below. I’m trying to cast as wide a net as possible in my research and every lead helps!

“THIS YEAR FOR ME HAS BEEN A DUST STORM”

For everyone finding creative work during the pandemic difficult or impossible, don’t miss this from the playwright and actor Tracy Letts in the New York Times:

TRYING TO GET TO 10K

For some reason, Instagram won’t let you share links in your stories until you get to 10,000 followers—and I would really like to be able to share links in my stories! Help me get to the magic 10K number by giving me a follow? That is, if you can stand to look at this handsome good boy on the regular…

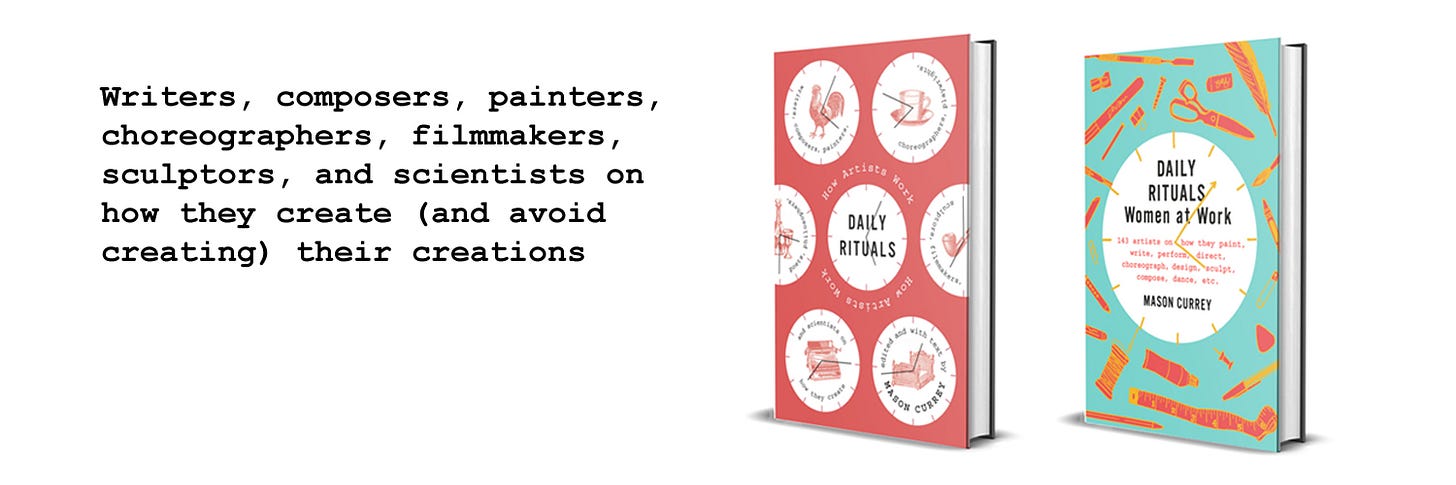

Thanks for reading! This newsletter is free, but if you’re feeling generous you can support my work by ordering my Daily Rituals books from Bookshop or (if you must) Amazon.

This parenthetical has been revised to make it less confusing! To be clear: The title of this newsletter—Subtle Maneuvers—comes from a phrase in a Franz Kafka letter. The (working) title of my new book project—Time, Strength, Cash, Patience (which is also the title of this issue of the newsletter)—comes from Melville’s Moby Dick. It appears at the end of chapter 32, when the narrator steps back for a moment and laments that he can never do full justice to his subject matter:

Finally: It was stated at the outset, that this system would not be here, and at once, perfected. You cannot but plainly see that I have kept my word. But I now leave my cetological System standing thus unfinished, even as the great Cathedral of Cologne was left, with the crane still standing upon the top of the uncompleted tower. For small erections may be finished by their first architects; grand ones, true ones, ever leave the copestone to posterity. God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!

I want to read it NOW!

I’m excited about this book! I think musicians, particularly blues musicians, would be great sources for this book. For example, Furry Lewis was a street sweeper almost his entire life and John Lee Hooker worked at an auto plant while recording his first hit singles