Dear readers! Last time I wrote to you all, in July, I was wrapping up an eight-week, worm-themed summer course that I had concocted as an elaborate piece of self-help: I would break down, step by step, the habits that I needed to adopt in order to finally finish my next book. So did it help? I’ll tell you at the end of this email.

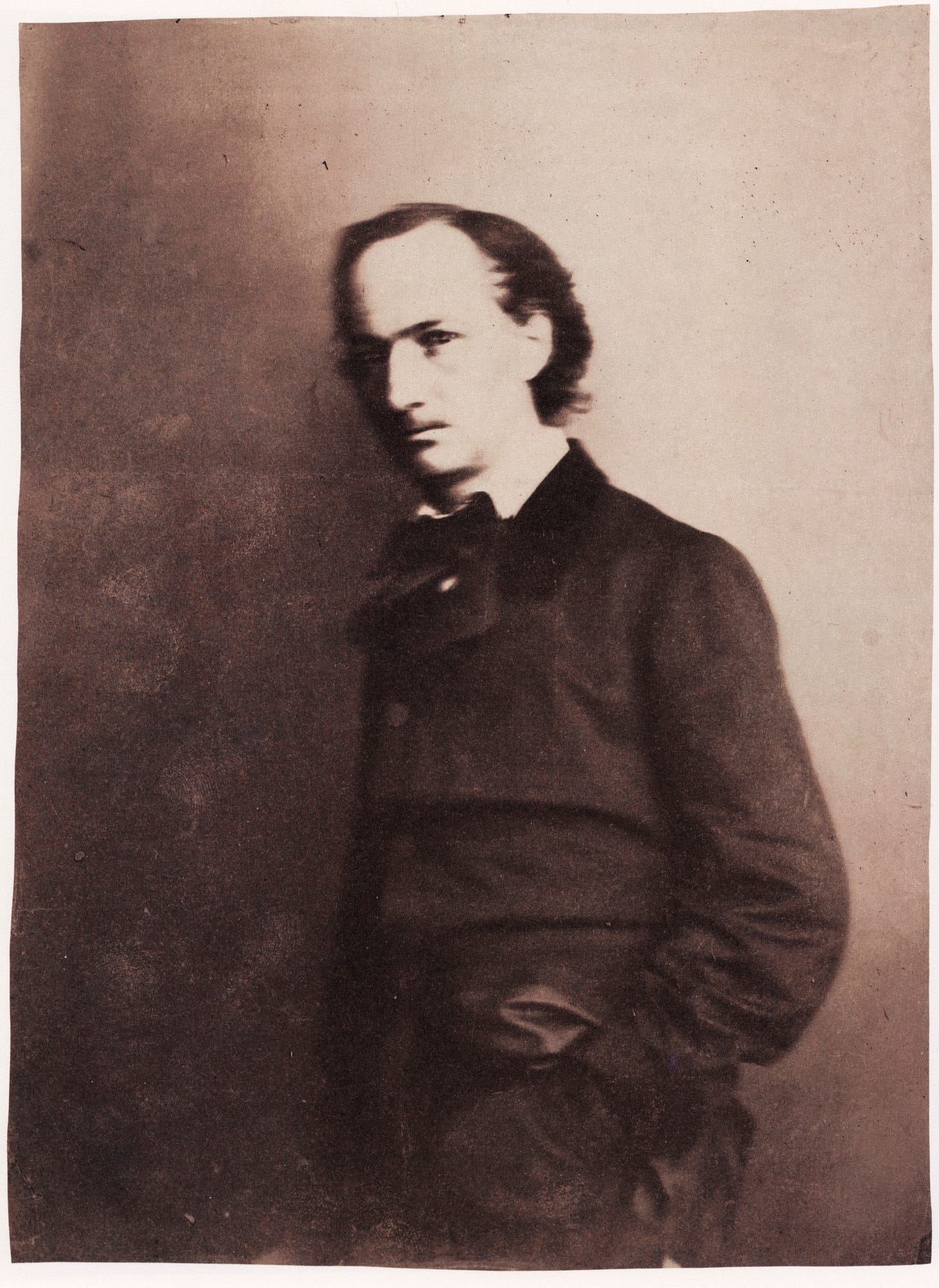

First, I wanted to share my great research discovery of the summer: the letters of the nineteenth-century French poet Charles Baudelaire, which I picked up from the library around the same time I was writing Worm School. Anyone who’s been following this newsletter knows that I can’t resist a tortured artist figure—and Baudelaire may have been the most tortured of them all?

As a writer, Baudelaire wanted “to crush people, astonish them, like Byron, Balzac, or Chateaubriand.” But he suffered from “terrible bouts of listlessness that disrupt everything.” Over and over, he admitted to wasting time, to letting the days slip through his fingers without applying himself to his projects. Along the way he became almost a scientist of procrastination, carefully observing the ins and out of his self-defeating pattern: