Welcome to the latest issue of Subtle Maneuvers—a loopier-than-usual issue, perhaps, because on Wednesday I turned in the first draft of my next book! And then I felt the most intense mental and physical exhaustion, something like if you ran a marathon and took the SATs on the same day, and went out for a very stiff martini afterward. But then I did a little reading for pleasure and here’s what I managed to eke out for today’s issue…

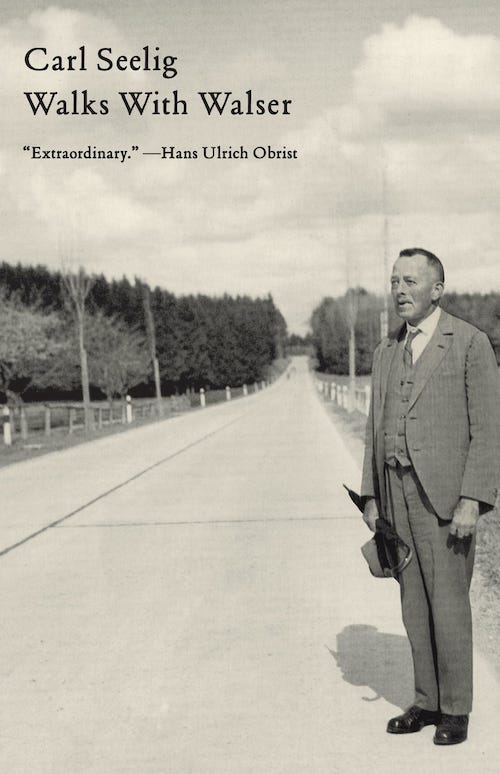

Robert Walser (1878–1956)

I love little books. You know the ones: closer to one hundred pages than two, with an appealingly slender profile on the shelf and just the slightest heft in your hands. I also love episodic books—one thing happens, then another, then another; I don’t really need it all to add up, or not explicitly. And, of course, I love books about the lives of writers and artists. So I was delighted last week to pick up Walks with Walser, a brief nonfiction account of one Swiss writer’s walks with another Swiss writer between 1936 and 1956, published in English in 2017.

The Swiss writer of the title is Robert Walser, who, the back-cover blurb informs us, “worked as a journalist, a bank clerk, a butler in a castle, and an inventor’s assistant and produced nine novels and more than a thousand stories.” The other Swiss writer is Carl Seelig, an admirer of Walser’s work who, in 1936, looked up the older writer and began accompanying him on daylong excursions through the Swiss countryside and beyond.

When the two writers first started walking together, Walser was living in a mental asylum, and he would continue to live there for the remaining 22 years of his life. The exact nature of his illness is difficult to pinpoint—according to his medical records, Walser “confessed hearing voices”—but, poignantly, it seems to have been precipitated by Walser’s failure to earn a living as a writer.